|

The second annual International Governance Workshop is complete. A small(ish) group of leading thinkers assembled at the Toulouse Business School in Barcelona to discuss and debate emergent research and to ask the "So what?" question. Overall, the presentations and papers were of a high standard, as was the discussion and debate that followed each paper. Also:

While this conference was amongst the smallest (in terms of delegates) that I have attended in recent years, the quality of the discussion and debate was amongst the highest that I have experienced anywhere. Senior academics openly interacted less experienced researchers and other attendees in the discussions, to the extent that it was hard to tell who was who unless you looked at the titles on name tags. From small beginnings in 2014, the TBS team has a clear vision of what they want to achieve. This second workshop built on the first workshop (I am told, I did not attend the first one), which augers well for the future. I commend this workshop to all academics, consultants, advisors and serving directors with an interest in board practice and business performance.

0 Comments

The deployment of complex technologies can be a demanding problem in modern societies, especially when various interest groups support or oppose such deployments. The magnitude of the challenge was not lost on Alfred A. Marcus (Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota). Using the example of implementing wind turbine systems as a source of renewable energy generation, Marcus compared the approaches taken in Texas and Minnesota. Both states have the high and relatively consistent wind runs considered to be a necessity for large farms of wind turbines. However, renewable technologies such are wind turbine farms are not universally supported. Some like the romanticism of the blades gently turning in the breeze; others assert they are a blight on rural vistas; and, yet others both like the idea but oppose local deployment (the pejorative NIMBY). Marcus observed that Texas' approach to decision-making and deployment was more top-down in nature, whereas the Minnesota experience was more bottom-up (and highly politicised). In considering this, he suggested that charisma without supporting regulation can lead to short-lived benefits. In effect, some ideas and decision processes need top-down 'support' to gain traction. Drawing on the work of Wilson (hierarchical decision-making) and Ostrom (collective action), Marcus proposed four 'rules' that can help, as follows:

In effect, Marcus' proposal was that a combined approach—incorporating hierarchical governance structures and decision-making processes and collectivism—was probably necessary if the not inconsiderable barriers to the deployment of complex and somewhat contentious technologies (like wind farms) are to be overcome. Although he did not explicitly extrapolate his comments, Marcus' suggestions are relevant and applicable to boards of commercial businesses. Many decisions, especially strategic decisions, fail to gain traction in implementation because a suitable framework for both decision-making and monitoring and verifying implementation is not established. Perhaps boards might like to consider Marcus' proposal, and see how it might apply. I suspect the answer in many cases will be 'well'—so long as a shared commitment to a common and singular purpose was in place.

The session that followed the challenging commentary of Silke Machold explored the place and role of regulation in corporate governance and, more specifically, in decision-making:

Neither speaker argued for more regulation, not did they argue for less. Rather, the challenge was a call to learn from the past and to do things differently. The thought-provoking proposal left delegates with much to ponder.

Prof. Silke Machold delivered the second keynote talk at the International Governance Workshop in Barcelona. Machold, who has been researching boards for many years, is a researcher that I admire—for she has been able to gain access to boardrooms to observe boards in action. Here's a summary of her rather wide-ranging commentary on companies and corporate governance:

Machold summarised her talk by suggesting that much has been said and claimed over the years, and that much of it had led to people getting quite excited about factors and attributes that, quite frankly probably are immaterial—thus the title of her talk: Much ado about nothing.

The topic of gender diversity on boards has received a lot attention in recent years. Researchers, interest groups and the media have chased various agendas. Much has been written and many claims have been made. However, compelling conclusions remain elusive. The topic received more attention during the first session of the second day of the International Governance Workshop in Barcelona. Three speakers presented the results of their research, conducted in the Polish and Spanish contexts. The studies explored variations on the theme of the impact of women on various financial and non-financial measures. All of the studies were quantitative analyses, conducted using publicly available data and statistical techniques. I have been critical of the use of such techniques for social research in the past. Reductivist approaches rarely provide insight beyond straightforward correlations. Sadly, I heard nothing to suggest otherwise in these talks. The challenge for board research is to move beyond the 'big three' assumptions--ontological reductionism, that a single objective reality might exist, and that a constant conjunction between variables constitutes a causal explanation—are inapplicable to board research, because boards and the context within which they exist, companies, are social constructions. Rather, the more demanding route, of qualitative research that explores boards in situ is more likely to reveal explanations that shareholders and director nomination committees can rely on. I remain convinced that women and people from a diverse range of background affect board practice. However, simple empirical research is not the appropriate pathway to understand and explain whether this is correct is not. More subtle approaches, that consider the context and behavioural nuances of individual directors appears to be crucial.

A panel of three very capable thinkers offered conference delegates insights into boards; board practice; and, continuing tensions between calls for corporate governance reforms in emerging markets, vibrant cultural differences and inconsistent capital market pressures. a summary of the insights and comments offered by panel members Thomas Clarke (UTS, Australia), Anderson Seny Kan (Université de Toulouse, France) and David Zoogah (Morgan State University, Baltimore, USA) follow:

While the three panel speakers observed many idiosyncrasies between emerging markets and with developed Anglo–American economies, a common thread emerged during the discussion. In most cases exogenous forces have held much of the power but this is starting to change. The role of the company in each economy is pivotal, both to the effective and fair operation of markets, and to contribute to the well-being of all citizens. While the panel members did not explicitly focus their comments directly on corporate governance, the linkages and implications for boards were clear: that company leaders and boards have a crucial role to play in the development of emerging economies, and that role needs to be taken seriously.

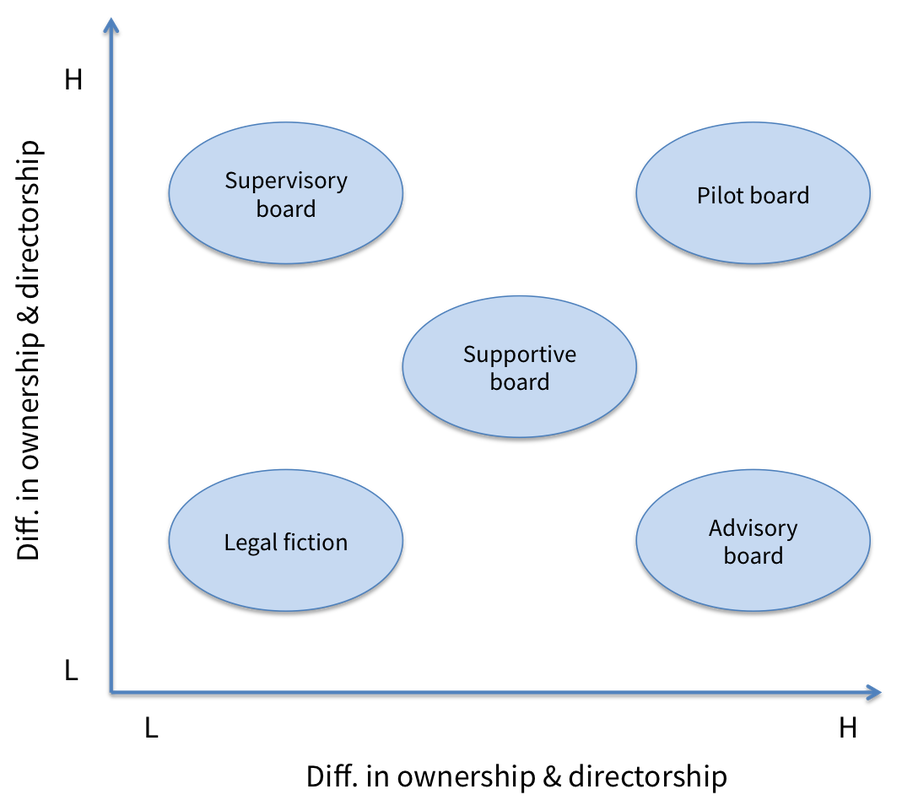

A team of researchers from Spain, France and New Zealand have been collaborating on an interesting project: one of understanding how board roles and contributions change in different firm circumstances. Khlif, Karoui and Ingley have identified five 'roles' that appear to emerge as firm circumstances change in two dimensions, as follows: The difference in the way the boards work (in terms of performing control, service, strategy and mediating tasks) appears to vary quite markedly when the difference between ownership and directorship is high (the directors are not owners), and when the difference between ownership and management is high (the managers and directors are not the same people). The paper offered some interesting insights relating to the emergence of corporate governance as a system within SMEs, and highlighted the need for a holistic, integrated consideration of board roles and board research, one that takes the company objectives and configuration into account. The research, to understand what this insight might actually mean is continuing apace.

The second International Governance Workshop got underway at Toulouse Business School, Barcelona Campus on Thursday 11 June 2015. Professor Morten Huse, an esteemed corporate governance scholar from Norway, provided the opening day keynote. Huse has been studying boards for a long time—the mid 1970s—so when he speaks, people tend to listen. Here's four of the points from his talk: Huse's talk set the scene for a lively debate through the balance of the conference. It will be very interesting to see how this develops.

The annual International Governance Workshop, hosted by the Toulouse Business School, starts tomorrow in Barcelona. Although only in its second year, this conference is an important gathering because it has attracted many of the world's leading corporate governance and board researchers. To be in the same room as these people, to hear them present and debate the results of emergent research is truly an honour. In contrast to the scale of the ICGN annual conference, the IGW is more intimate and more focussed. However, the programme of topics to be explored is no less significant. Session summaries will be posted here, as usual, so you can keep up to date. My paper will be delivered on Thursday afternoon.

Every now and then, a great article crosses my desk—one that seems to lift itself off the page, as if to command attention. This is one such article. Writing in The Economist, Schumpter comments on an idea promoted by Boston Consulting Group: that dexterity is increasingly important in today's fast-paced world. The assertion is that modern companies need to be adept at skipping nimbly between strategies or types of strategies (or to commit to multiple strategies simultaneously). Five types of strategy are identified, as follows:

The article makes plan the challenge moving between strategies, especially with management reputations and careers on the line. One option to resolve this challenge might be for boards to focus directly on leadership and strategy because the task of developing strategy has become so important to business success. A return to the historical conception of strategy--strategos, the art of command—is appropriate. (Many business academics and boards of directors consider strategy to be an important task of the chief executive.) If boards become more strategic, by contributing expertise and challenging strategic options, then 'ownership' of both strategy and the outcomes that flow is likely to move to where it actually belongs--in the boardroom.

|

SearchMusingsThoughts on corporate governance, strategy and boardcraft; our place in the world; and other topics that catch my attention. Categories

All

Archives

February 2024

|

|

Dr. Peter Crow, CMInstD

|

© Copyright 2001-2024 | Terms of use & privacy

|