Roger L Martin, a respected professor at Rotman School of Management and co-author of Playing to Win, has put the cat amongst the pigeons, with this commentary, itself a response to this widely circulated article. The authors of the original article reported findings from a study, which showed that only eight per cent of leaders are good at both strategy and execution. Martin contends that most leaders who are very effective at either strategy formulation are also very effective at execution. Quite a different view. Two different perspectives. Who is correct? As with any report involving statistics, context is crucial. If you consider all leaders (as Leinwand, Mainardi and Kleiner did), only eight per cent are "very effective" at both formulating strategy and executing strategy. However, if you only consider only those that are "very effective at strategy", fully two-thirds are also good at execution (Martin's point). Thus, both authors are 'correct'. But which commentary is more helpful to leaders and those intent on achieving business success? The shocking statistic is that just sixteen per cent of leaders are "very effective" at strategy formulation or execution or both. Turbulent times demand outstanding leadership, both to determine strategy and to ensure it is executed with excellence. Poor, neutral and even "effective" contributions have little chance of moving companies toward their goals if they are competing against "very effective" leaders. Consequently, 84 per cent of leaders will be found wanting (notice the Pareto Principle?). Rather than debate statistics, it may be more useful to move the discussion to discovering how to move more leaders into the "very effective" sector. Another perhaps more important question—for boards of directors in particular—centres on Martin's assertion that strategy and execution are the same thing. Can the two tasks can be distinguished? Strategy formulation and execution are two of the four pillars of strategic management (development, approval, implementation and monitoring). My research suggests that business success is dependent on two things: having a clear sense of purpose and an effective strategy, and great execution. The former is an important task that boards and managers should work on together and the latter is the domain of management (only) once strategic decisions are made by the board. However, some flexibility is required because things change. Decisions and adjustments are required from time to time. If companies are to react and respond quickly, strong leadership is crucial to avoid mayhem. So where does that leave Martin's assertion, that formulation and execution cannot be usefully distinguished? What is your experience?

0 Comments

Much has been made of the value of board 'going digital' in recent years. Many software-based systems have been produced including offerings from Boardpad, Diligent, Boardpacks and Board Management, amongst others. The benefits of these systems are reasonably self-evident: improved coordination and management of board reports, reduced administrative costs and improved security, not to mention far less weight to carry to and from meetings. However, 'going digital' is not without its challenges. Some perhaps less credible claims have been made about software-based systems for boards, leading to misplaced optimism. Take the promise of increased engagement for example. Glance around the table at your next meeting. How many directors are listening intently, fully engaged in the discussion, and how many are covertly checking their devices for messages? Engagement with devices and systems has certainly gone up, but what of engagement between directors and with the topic at hand? In my experience (hundreds of board meetings over the last fifteen years, as a director or an observer), the task of direction is a full-time commitment requiring total concentration, especially if the board is large and/or the topic at hand is complex. It's a tough job, with a hidden twist to boot. While directors attend board meetings, they don't make decisions—boards do. If directors are to do their job well, they need to express their opinions and concerns; ask questions; debate topics; listen carefully (to hear both what is being said and what is not being said); and, depending on arguments raised, they may need to gather more information and modify their opinions. Messages on electronic devices can wait. While computer- or tablet-based board productivity systems can improve the administrative aspects of board meetings (and greatly so), directors cannot afford to be at their beck and call. They provide no substitute for discussion, debate and collaboration as directors meet together to carefully consider important matters and make decisions. Let's not forget that. [Postscript: Technology and devices are appealing. I get that. I'm happy to support the introduction of any system that improves director effectiveness. The challenge for directors is to learn how to use systems well, so they can concentrate on what they are actually there for—to make decisions.]

As 2016 gets underway, have you given any time to making sure your knowledge of boards, board practice and corporate governance is up to date? If not, I'd like to offer a suggestion. One of the more heavily thumbed texts on my bookshelf is Corporate Governance: Principles, Policies, and Practices (2nd ed.), by Bob Tricker. This 550-page volume describes the nature, structures, functions and operating realities of boards and governing bodies; the major aspects of corporate governance; and, corporate governance theories. Other issues that influence board thinking including strategic risk management, corporate social responsibility, ethics and sustainability are also discussed. Others have contributed much to what we know about corporate governance, boards, what boards do and how they work. Yet Tricker stands apart. Sir Adrian Cadbury once said, "I have always regarded Bob Tricker as the father of corporate governance since his 1984 book introduced me to the words corporate governance." High praise indeed. Now, a third edition has been published (available here). If the value and practical application of the ideas in the second edition is any measure, the third edition is a 'must read' for all chairmen, directors and company secretaries, everywhere. I commend this seminal contribution to you.

Guest blog: Guy Le Péchon (Gouvernance & Structures, France) Board rejuvenation is often considered and discussed, but statistics on boards member ages show little progress. The general public thinks a board of directors is a set of relatively old people. Common sense and corporate governance approaches lead one to think that the introduction of new ideas from younger generations would surely be a company asset.  Age diversity within a board is unquestionably desirable, but will one or two younger directors be enough? Probably not. In fact, except in exceptional cases (mainly in new technology fields), board members will probably be least 35 years old—hardly 'young' any more—by the time they have acquired the experience needed to be a skilled board director. Also, younger leaders often have full-time jobs, so will there be sufficient candidates available anyway? Recruitment of younger directors may be difficult and generally will not be enough to ensure that potential contribution from truly young people will be brought to the boards. How then to proceed ? One approach to solving this problem might to be create a Young People Board, under the leadership of the official board—a 'shadow cabinet' of sorts. With slightly different goals, some municipalities use this approach. A Young People Board could be composed of 18 to 25 year old volunteers—a similar number of members as the official board. Recruitment could be for three-year terms (with renewal of one third every year). The aim would be to achieve multi-faceted diversity. Periodically (say three times per year), the company board would invite the Young People Board to consider a topic discussed by the official board. The Young People Board would meet to debate the topic and develop proposals. Many ideas would emerge as young people naturally consider new technologies; social networks; data protection; ecology; ethics; and, international perspectives. Each year, a half-day meeting would be scheduled with the official board, to receive presentations and debate the topics studies by the Young People Board . The Young People Board formula would be light, without any significant expenses or time commitment from the official board members. However, the process would enable official board members to be positively confronted with new ideas coming from truly young people. They may even retain some ideas for implementation! Members of the Young People Board and, indirectly, their friends and relatives, would derive benefits including learning about the company activities, its executives and, importantly, the 'corporate governance' world. Through the process, the company may identify young talents for later hiring. The company could use this approach to improve its image, especially among young people. Many speeches and writings advocate innovation. As one dwells on this, the realisation that innovation applies not only within technology areas, but also in organizational processes and the social domain. The Young People Board is a concrete example of this type of innovation. Is this something your board can support? If so, please contact Guy Lé Pechon at Gouvernance & Structures. Guest blog: Guy Le Péchon (Gouvernance & Structures, France)

Have you noticed how 'corporate governance' has pervaded the modern lexicon? The term is used in all manner of contexts nowadays. Some are appropriate and some less so. I wrote about this last year, off the back on a comment made by Rob Campbell. Here's a couple of fresh examples that I've heard used in the last sixty days:

Both of these examples might sound a little contrived, but they are not. All three phrases were spoken, spontaneously and in my hearing, by capable and well-intentioned people. The people in the room knew what was meant, I think. However, these three vignettes set me thinking. Is our usage of the term 'corporate governance' starting to change—away from the original intention (describe the functioning of the polity, i.e., the board of directors) to something different, or have we become somewhat lazy in our usage? I'd be interested in your views on this one!

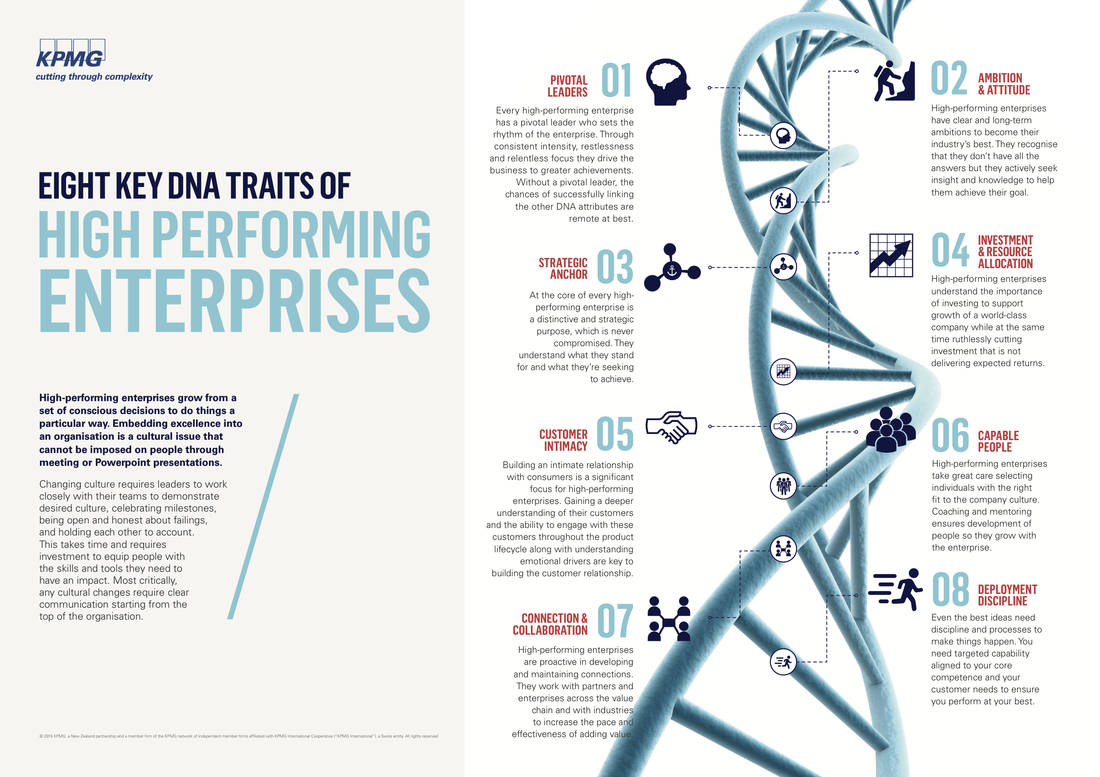

What makes a successful business successful? Can success be pursued, or are great outcomes largely a matter of luck? Success, it seems, is dependent on companies doing a rather small number of things consistently well. Jim Collins (Good to great), Colin Campbell-Hunt (World famous in New Zealand) and others have studied this question and produced some great insights. Recently, business advisory firm KPMG, added their view. The KPMG study revealed eight 'DNA traits' of high-performing enterprises, as follows (click image on right for a larger version): This guidance is as applicable to smaller companies with big dreams as it is to more mature companies wanting to defend against competitors or push on to the next level. Did you notice that a having great product or a killer app—often lauded as being 'the crucial difference'—does not rate a mention? This point has interesting implications for strategic management, and strategy development in particular. While good products and services are important, leadership, people (customers and team), smart decisions and a sense of purpose are far more significant moderators of business success. If you'd like to discuss the implications of these observations for your board or your corporate strategy, please get in touch. I'd be more than happy to be a sounding board.

As 2015 gives way to 2016, many people will be reflecting on the past and looking to the future; thinking about what was and what might have been. I'm no different. One of the books I've been reading while pondering the past and the future this week is The Servile Mind by Kenneth Minogue. A friend recommended it—he wondered whether the commentary might be applicable to directors and boards. My response, having read half of the book so far, is an unreserved 'yes'! Here's the note on the flyleaf: One of the grim comedies of the twentieth century was that miserable victims of communist regimes would climb walls, sim rivers, dodge bullets, and find other desperate ways to achieve liberty the West at the same time that progressive intellectuals would sentimentally proclaim that these very regimes were the wave of the future. A similar tragicomedy is playing out in our century: as the victims of despotism and backwardness from Third World nations pour into Western States, academic and intellectuals present Western life as a nightmare of inequality and oppression. In The Servile Mind: How Democracy Erodes the Moral Life, Kenneth Minogue explores the intelligentsia's love affair with social perfection and reveals how that idealistic dream is destroying exactly what has made the inventive Western world irresistible to the peoples of foreign lands. The Servile Mind looks at how Western morality has evolved into mere "politico-moral" posturing about admired ethical causes—from solving world poverty and creating peace to curing climate change. Today, merely making the correct noises and parading one's essential decency by having the correct opinions has become a substitute for individual moral responsibility. Instead, Minogue argues, we ask that our governments carry the burden of soling our social—and especially moral—problems for us. The sad and frightening irony is that the more we allow the state to determine our moral order and inner convictions, the more we need to be told how to behave and what to think. Humbly, I commend this book to all directors who want to govern well and make a difference in 2016.

|

SearchMusingsThoughts on corporate governance, strategy and boardcraft; our place in the world; and other topics that catch my attention. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

|

Dr. Peter Crow, CMInstD

|

© Copyright 2001-2024 | Terms of use & privacy

|