|

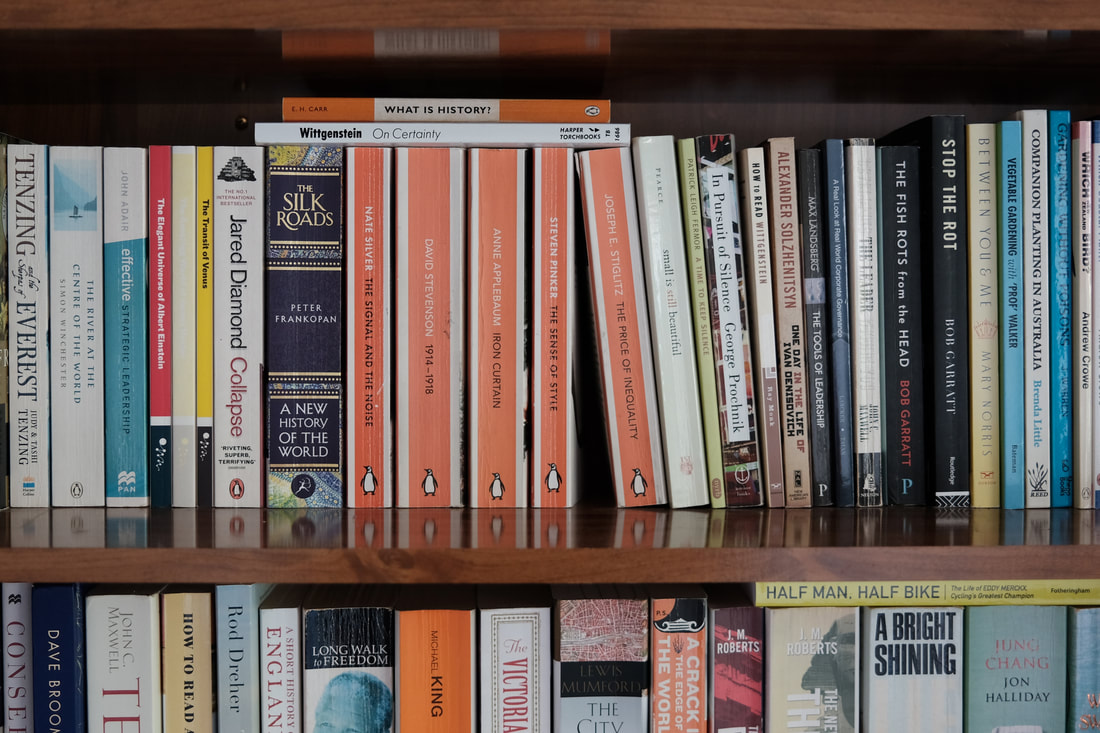

I have the good fortune of meeting many hundreds of people every year—aspirational and established directors, board chairs, executives, journalists, shareholders, MBA students, doctoral candidates, lobbyists, regulators, policy analysts, conference organisers, and more besides. Sometimes, contact is fleeting; sometimes it is enduring, as we work together to gain insight, educate, or tackle a difficult problem. One question that keeps coming up (besides the big three, namely, what is corporate governance; what is the role of the board; and, how should governance be practiced) is, "How do I stay current and relevant?" The answer is straightforward. I read, a lot. Every morning—well, at least six days a week—I dedicate 90 minutes or more, to check newsfeeds, blog posts and emails that have arrived overnight. The primary goal is to ensure I have sufficient awareness to engage well with colleagues and clients on topical matters. Some people call this continuing professional development. I prefer a simpler description: reading to keep up. This commitment is, I find, a bare minimum because it does not afford space to read widely and think deeply about ideas, perspectives and the human condition. For that, I read books; sometimes in the evenings, but most often on flights and during holiday breaks. Why? Because I have time to think and mark (in pencil in the margin if a physical book, or electronic bookmark if an e-book) specific points to investigate further. Several people have asked what I'm reading. Here is a list of books either under way or to be read this summer break. Notice only one is directly linked to my board and governance work. That is intentional. Reading widely means, to me, reading beyond normal boundaries to discover new ideas and ways of thinking about things. This list is a selection of the books awaiting my attention. If you read, I'd love to hear any recommendations!

0 Comments

The sharing of knowledge with clients and conference attendees is an activity that I find very fulfilling, mainly because it is a two-way activity. Be it facilitating a professional development course, speaking at a conference or dinner event, or facilitating a private learning workshop, the opportunity to both share knowledge with and learn from attendees is one to be taken seriously. On several occasions recently, I have had the privilege of seeing this operate at yet another level: a team-based delivery model whereby two presenters work together to share insights, answer to questions and learn from the assembled group. The positive response from attendees to a team-based model was a sight to behold. The levels of engagement; esprit de corps; and, quality of learning amongst the assembled group (not to mention the banter between the presenters) really lifted the learning experience. The following examples provide windows into two of my recent experiences, and then the learnings to emerge follow. Rural Governance Development Programme Earlier this year, Peter Allen of Business Torque Systems invited me to join a team to refine the five-day Governance Development Programme (a popular course previously run by DairyNZ for dairy businesses) to suit all of rural businesses. In updating the course, a decision was made to use a team-based delivery model, with two presenters working together with attendees. The hope was that this would provide better coverage of the material, as well as enabling attendees (directors, shareholders and chief executives of rural businesses) to a hear different perspectives as the course progressed. And so we jumped in... We resolved to work from the front of the room together, sharing the speaking and listening roles... We stepped aside, to check in and make adjustments... This picture, taken on the third day (of five—the course days are spread over a ten-month period so delegates can apply their learning in practice and bring questions and experiences back to the next session), captured us discussing a couple of 'in-flight' adjustments while participants worked on an exercise to improve their strategic decision-making skills in a boardroom setting. Health sector board member development workshop The second example relates to the delivery of a professional development session for the board members and executives of three primary health organisations (PHOs). They wanted a refresher on board effectiveness and strategy in the boardroom—topics dear to me. The organiser was keen on a two-person delivery model as well, which created another opportunity to explore and experience the effectiveness of the team-based model. I organised to work with a trusted colleague, Murray. We know each other well and share a commitment to excellence but have slightly different styles. After introductions and scene-setting, we asked the group to tell us what they wanted to get from the session and to mention specific areas of interest. Then it fell on me to lead the first session (board effectiveness) with Murray chipping in regularly to help answer questions and share examples from his experience. The roles were reversed for the second (strategy) session later in the afternoon. Finally, we jointly ran an free-flowing plenary session to check all of the areas of interest had been addressed and answer any remaining questions. Learnings Feedback from the attendees (informal plus evaluation sheets) from both the rural course and the health sector learning session indicated that the double-teaming model works. Attendees said they got more from the session than they thought they might have gained had there been one presenter. They could listen to and tell stories to connect ideas with practice; ask similar questions and get a different (!) responses; and, they said they benefitted from tapping into a broader pool of knowledge and experience than what would otherwise have been possible. One board member went as far as saying that the session was "the best learning session ever organised by <PHO-name omitted>", gratifying feedback indeed. The levels of trust and interaction in the room in both the rural course and the health sector session were also noticeably high. (Whether this is a reflection of what is being modelled from the front of the room or it is simply an expression of the delegates' innate character and desire to learn is open for debate!) Where to from here? Though not without its challenges (working so closely together requires considerable planning and trust, for example), the early experiences have been positive. There is also a 'cost' of putting two people in the room. However, the benefits in terms of enhanced learning outcomes tip the balance in favour of the team-based model—especially for advanced topics and multi-day courses. The learning theorists are probably all across this, so I'll need to play catch-up. If you have any experiences to share—positive or negative—I'd be keen to hear from you. Please respond by posting a reply or send me an email.

When I was in London most recently, in June, I fortunate to visit Greenwich. A friend had told me that Greenwich Village is 'different' and that a visit was in order. And it was! In contrast to the hustle and bustle of the City, Canary Wharf and the West End, the people of Greenwich are more laid back. They smile, they say 'hello' and they walk more slowly than their neighbours across the Thames. Many, like the twelve in the picture, happily sit and peer into the distance, taking it all in. Who knows what they were thinking or even looking at. It probably doesn't matter, I guess. Why am I relating this story? My short visit occurred three-quarters of the way through a hectic three-week multi-country trip. It reminded me of the importance of downtime. With hindsight, the interlude—to gather my thoughts—probably made the difference between just making it through the final week of the trip, and finishing the trip well. Today, as I was working on a presentation to be delivered on my next trip (1–11 September), thoughts of that Greenwich interlude entered my consciousness. The upcoming trip is packed with seventeen significant commitments including two master classes, three presentations, two important dinners and several planning and roundtable meetings; in London, Canterbury, Leeds, Wolverhampton, Dublin and Belfast. It'll be a busy trip. To top it off, our elder son, who is working in Germany at present, has just asked if we can meet up in London while I'm there. Of course, but when? Then the penny dropped. Rather than pursue two remaining 'pencilled in' meetings, why not spend an afternoon with Tim? Two carefully crafted emails later, some 'Greenwich Time' was locked in. I'm looking forward to it already. As you move through Friday, my hope is that you too will have the opportunity—better still, take the opportunity—to run on Greenwich Time this weekend. If we are to perform well when it counts, we need to set time aside to relax, recharge and to prepare—mentally, physically and spiritually—for that which lies ahead.

Well, ICMLG is over for another year. The ACP organisation, and hosts Babson College (Phil Dover and Sam Hariharan, in particular), organised a great conference. Delegates assembled from over 20 countries from the five major continents. The theme of entrepreneurship provided a linking thread between the keynote speakers (Isenberg and Schlesinger), the paper streams and many conversations over coffee and food.

I particularly enjoyed the provocative sessions of Isenberg and Schlesinger, and appreciated the opportunity to test some of the ideas that are emerging from my research, especially with researchers from outside the Anglosphere. That feedback will result in some adjustments to the way that my thesis is written up. To everyone who offered feedback: thank you! I commend this conference to all management, leadership and governance researchers, and practitioners with an interest in these and related fields. Next year, the conference venue is in the southern hemisphere, in Auckland New Zealand. The co-hosts will be AUT and Massey University. Certainly, I am looking forward returning the hospitality afforded to me in the international conferences that I've been fortunate enough to attend in the last couple of years. I had a fantastic meeting with my PhD supervisor earlier this week, to review my approach to the research methodology chapter of my thesis. When we stopped for some lunch and a walk outside, James showed me two articles from the 19 October 2013 issue of The Economist. They blew my mind. Entitled How science goes wrong and Trouble at the lab, the articles outlined how much of the so-called scientific research conducted by academics is actually a load of rubbish. For example:

The examples and supporting narrative floored me—it was sobering reading. The points about how research is conducted, how research articles are reviewed and, most importantly, how research is funded (the funding mechanisms drives the behaviours) were enlightening. The lingering question in my mind, having dwelt on these articles over the last two days, is this: just what research can we accept then? The answer probably lies in the maxim recorded in the first sentence of the 'goes wrong' article: 'trust, but verify'. The exercise was a timely and helpful wakeup call for my own efforts, to ensure my work is 'good science'. Thank you James. Periodically, I'm asked whether I'm an advisor or a consultant. For many years now, the answer I've provided has been 'advisor', often in an effort to avoid the stigma commonly associated with 'consultant'. (Consultants are the guys that borrow your watch to tell you the time, right?) However, as I've studied the English language more closely in the last couple of years, I've become much more comfortable with the term 'consultant', because it most accurately describes who I am and what I do. Let me explain.

Generally speaking (although perhaps somewhat simplistically):

While my priority as a pracademic is to think broadly about corporate governance and strategy in order to discover possibilities and pursue options, my clients are most interested in solutions to problems they face today – recommendations and answers – which fits nicely with my instinct to understand and solve problems. Now your turn: Are you an advisor or a consultant? Every now and again, an article lifts itself above the many that I read each day to capture my attention. This one is one of those. It is short, easy to read and, crucially, on the money.

A couple of correspondents have noticed (and commented!) that my dispatches from the ANZAM conference, held in Hobart 4-6 Dec, appeared to be incomplete because the last dispatch posted covered the keynote at the beginning of the second day. Indeed, this is correct. Most of the leadership and governance papers that I was interested in were presented on the first day. I spent much of the second day in one-on-one discussions with other researchers, exploring ideas that had been presented earlier in the conference, and testing a few ideas of my own. This proved to be a very valuable albeit more private time for me, because I was able to correct a few assumptions and misunderstandings, and get some additional clarity on some concepts that I didn't grasp well when they were first presented.

One session that proved to be very interesting was the interactive session on management education and the rise of MOOCs (massively open online courses). This new concept, of an entire course of material delivered online has caught the attention of many. The concept sounds great on paper, particularly to extend reach. However, the delivery model is not without its challenges (no opportunity to interact with others to thrash out ideas on a whiteboard, for example), and the financial model needs work (currently, access is free). Notwithstanding these points, the concept has merit as a delivery model alongside others. MOOCs should not be regarded as a panacea to replace the traditional (though high-cost) classroom learning model, as some have suggested. Overall, the conference met my expectations. It was well-organised, with plenty of opportunity to interact with other delegates. However, the quality of the papers was lower than I expected. Some described some simply outstanding pieces of research, but, many others were straightforward reports of statistical analyses of readily available data. Papers in this category lacked any insightful commentary to assist future research, or help managers improve their performance in the field. In my opinion, some of these papers should have been rejected at the review stage. A smaller collection of higher quality papers makes for a better conference. If this shortcoming can be addressed, then the appeal, relevance and usefulness of ANZAM—to researchers and managers alike—will be enhanced I'm sure. Today is the first Thursday I've had to myself since 14 February. I have been teaching 115.108 "Organisations and Management", a first-year paper at Massey University. This was my first teaching experience in an undergraduate environment, so I didn't really know what to expect. Would the students engage? Would they just sit there? Would they even turn up?

Fast forward to today. The semester is complete, save the final examinations. Having now completed the assignment, I've learnt a lot—about myself, the students and the learning environment—so thought a few reflections would be in order:

Acclaimed businessman, Rob Fyfe (formerly CEO of Air New Zealand), was reported this week as saying that business students don't understand leadership in the real world, and that universities should take a more authentic approach to leadership study. I agree.

Over the last two years, I have been immersed in post-graduate study—initially a post-graduate certificate in business, and subsequently doctoral study. In so doing, I have observed some rather interesting behaviours and patterns that, quite frankly, trouble me.

The consequences of these behaviours and patterns appear in the assignment submissions, theses and research reports produced by students and faculty. Much of the material is technically correct but either hard to understand or lacking in any applicability to real-world situations. It's almost as if the "so what?" question has never been posed, let alone wrestled with. In my opinion, all aspiring business students should be required to undertake at least five years practical experience in a relevant field before they are accepted into any post-graduate programme. Also, faculty should be required to do a significant period of field work on at least a sabbatical basis (every seven years). This type of requirement would ensure students and staff have at least a basic understanding of business in the real-world. Such a model may well be threatening to some faculty who sit comfortably in their learned environment. However, I suspect the quality and practical usefulness of the research produced, and calibre of graduates re-entering the workforce, would increase markedly. What do you think? |

SearchMusingsThoughts on corporate governance, strategy and boardcraft; our place in the world; and other topics that catch my attention. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

|

Dr. Peter Crow, CMInstD

|

© Copyright 2001-2024 | Terms of use & privacy

|