|

Questions of where we came from, why various things happened or evolved as they did, and what we can learn from them to guide us as we live our lives fascinate many people—me included. From neo-lithic henges and stone circles, to the development of more recent industrial-scale enablers (notably, the wheel, the printing press, manufactories, the motor car and the Internet), man has long been fascinated with history, innovation and possibility. When we ponder historical developments and innovations such as the examples noted here—and other foundational things like language, writing, mathematics, ethics and civics—we gain insight to apply in our daily lives or use as a springboard to try to make new discoveries. This maxim applies personally, in family and social groups, and more broadly in society—and if we ignore it, it may be to our peril. The idea of learning from those who have gone before us is applicable in organisations too. How else would individuals and teams know what to do? This is what learning and development departments organise, and why professional development programmes exist. In the realm of boards and boardwork, relevant questions include three I have been asked most often over the past two decades: What is corporate governance; what is the role of the board; and, how should governance be practiced? That these questions are asked so often suggests directors (at a population level) lack the knowledge needed to be effective. Helping directors and boards govern with impact is a calling for me, so when Mark Banicevich invited me to explore the history of corporate governance—well, make a fleeting visit across a few high points in the Western context—I jumped at the chance. Hopefully, the commentary is helpful. Do let me know whether you agree or disagree with the various perspectives, and why, because I’m no Yoda (use the comment section below, or contact me directly). Life is a learning journey for me as well!

0 Comments

Recently, I had the great fortune to sit with Mark Banicevich, a business leader, to record a set of three fireside chats for his Governance Bites series. Mark was keen to get my take on several topical aspects of boards and governance. The first of the three conversations is now available to watch. (The second and third conversations in the series will be posted in April and May.) In this conversation, we explored board work in various jurisdictions, noting differences and similarities along the way. While a 20-minute whistle-stop conversation is hardly sufficient to do the task justice, I do hope it encourages you to explore further, and is a catalyst for some conversations. And, may I ask... is the commentary helpful or not? What do you agree or disagree with? I'd be glad to hear your thoughts, either in the comments section below, or directly, if you prefer. The end of 2023 is nigh; consequently, minds have turned to end-of-year celebrations, various secular and religious festivals, and, inevitably, reflections. Twenty twenty-three has been a standout year for me for several reasons, not the least of which have been many expressions of encouragement, support and endorsement as I have sought to help boards govern with impact. That I have had the opportunity to contribute is a delight. But more than this, the seemingly simple fact that directors, boards, shareholders, institutions and others invite me to advise, assess, educate, speak and otherwise provide counsel, is a great honour. Thank you to everyone who has sought me during the year and entrusted your situations to me. These are cherished interactions. As I sit back, in these final hours of the 'business' year, I have found myself pondering 'reach'. This, a response to a question from a friend who, knowing of my recent trip to Kenya, wanted to know how many countries I had visited in 2023. When I checked back, this is what I discovered:

Superficially, this sounds like a busy year. And it has been. But, I hasten to add these data are neither targets nor badges of honour. They are, simply, footprints: evidence of my travels as I have sought to help boards govern with impact over the past year. Looking to 2024, my intent is to continue to serve—subject to boards and directors wanting guidance, of course! For now though, my objective is more selfish: it is relax, read and recharge, in readiness for what lies ahead. Best wishes as you close out 2023, and turn the page to reveal 2024.

Do you have a question about governing with impact, or driving organisational performance?22/8/2023 One of the great joys of being an independent advisor is the opportunity to spend time with people from a wide range of backgrounds; business and social experiences; walks of life; and, in my case, countries and cultures. The depth and breadth of humanity never ceases to amaze me. Paradoxically, a common thread runs amongst the diversity: people intent on improving organisational effectiveness and making a difference spend lots of time asking questions, lots of questions. When a question is asked from the floor after a keynote talk, during an advisory engagement or professional development workshop, or as part of a confidential discussion or informal chat, something mysterious happens: Both parties learn! This should come as no surprise, for no one has all the answers—although some people behave as if they do. Recently, I posed several questions board directors may wish to consider. The response to that musing has been overwhelming, so I thought an open invitation might be in order. If you have a question about any aspect of corporate governance, strategic management, board craft or the challenge of governing with impact—either personally or on behalf of a board you serve on—please ask and I will gladly respond. Use the comment link here or, if you prefer, send an email. Let's learn together!

I have spent four days in Australia this week, meeting with directors, advisors and a couple of institutional leaders in two state capitals. While the weather has been great, a few storm clouds [metaphorically, on the governance horizon] were apparent. Whether these are serious problems, or just differences of opinion, they strike me as being worthy of discussion. I’d be delighted if you would ponder the following situations, and share your thoughts to help me understand why boards, more often than not, erode value.

These examples demonstrate, to me anyway, that questions of what corporate governance is, the role of the board and how governance might be practiced are far from resolved. Directors and their advisors seem to be their own worst enemies. Flawed understandings of what governance is (the provision of steerage and guidance, to achieve an agreed strategic aim), and how it might be practiced, remain serious barriers to boards fulfilling their mandate, which is to ensure the enduring performance of the company. Why do some directors’ institutes, advisory and consulting firms, regulators, academics, and media commentators continue to discuss “best practice” and promote various matters that have little if any direct impact on achieving sustainably high levels of organisational performance? Surely attention needs to be on helping directors and boards do their job well, n’cest ce-pas? I have a few ideas to crack this problem, but I’m keen to hear what you think.

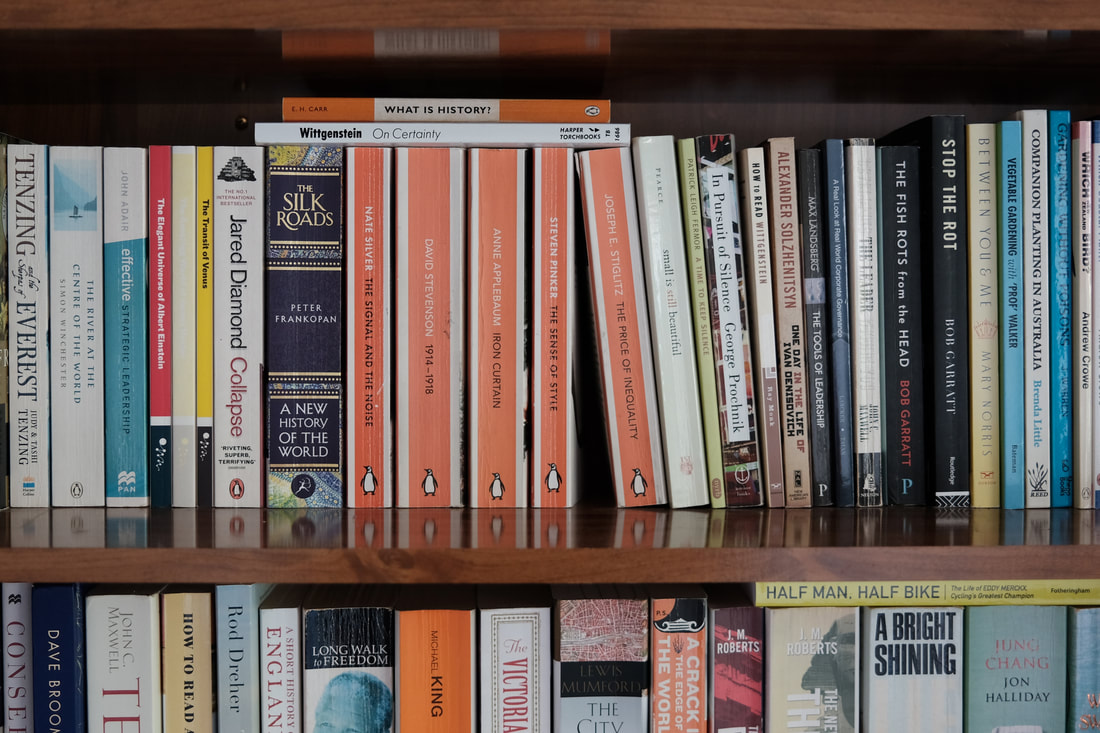

I have the good fortune of meeting many hundreds of people every year—aspirational and established directors, board chairs, executives, journalists, shareholders, MBA students, doctoral candidates, lobbyists, regulators, policy analysts, conference organisers, and more besides. Sometimes, contact is fleeting; sometimes it is enduring, as we work together to gain insight, educate, or tackle a difficult problem. One question that keeps coming up (besides the big three, namely, what is corporate governance; what is the role of the board; and, how should governance be practiced) is, "How do I stay current and relevant?" The answer is straightforward. I read, a lot. Every morning—well, at least six days a week—I dedicate 90 minutes or more, to check newsfeeds, blog posts and emails that have arrived overnight. The primary goal is to ensure I have sufficient awareness to engage well with colleagues and clients on topical matters. Some people call this continuing professional development. I prefer a simpler description: reading to keep up. This commitment is, I find, a bare minimum because it does not afford space to read widely and think deeply about ideas, perspectives and the human condition. For that, I read books; sometimes in the evenings, but most often on flights and during holiday breaks. Why? Because I have time to think and mark (in pencil in the margin if a physical book, or electronic bookmark if an e-book) specific points to investigate further. Several people have asked what I'm reading. Here is a list of books either under way or to be read this summer break. Notice only one is directly linked to my board and governance work. That is intentional. Reading widely means, to me, reading beyond normal boundaries to discover new ideas and ways of thinking about things. This list is a selection of the books awaiting my attention. If you read, I'd love to hear any recommendations!

December is a significant month for many peoples around the world. It is the month in which two of the three great Abrahamic faiths have a major festival (Jews, Hannukah; Christians, Christmas), and the Japanese observe Omisoka. For others not professing a faith, December is significant to the extent that it marks the end of the Julian calendar. Each of these observances is distinctive, but a common thread runs through them: celebration and dedication. Yes, December is a time to reflect on the year gone and give thanks, and to ponder what lies ahead. Through this muse, I too wish to give thanks, to the many board directors, business leaders and students that I have had the good fortune to work with during 2021—both in person in New Zealand, and via video link in the United Kingdom, the European Union, the Caucasus region, North America and the Caribbean, India, several African and Middle Eastern countries, and closer to home in Australia. I have learnt a lot, and hope others have derived value from the interactions. Thank you. Peering into 2022, the prospect of travelling internationally to work in person with boards and students is enticing. Once the coronavirus situation stabilises, border restrictions are relaxed and travel becomes viable again, I will accept bookings. But in the meantime, I have decided to take on a new project. For over two decades now, I’ve had the privilege of working with aspiring and established directors on five continents, helping them wrestle with problems, consider opportunities, make decisions and learn what it means to be an effective director. Over the same period, two friends have encouraged—even nagged—me to consolidate my ideas, experiences and insights into a book. And each time it has been mentioned, I have pushed the idea away, citing lack of head space. But circumstances have changed in 2021 and the time now seems right to reconsider the prospect of writing 50,000 words about governance and the craft of board work. So, that is what I will attempt in 2022. (*) The image shows the Marsden Cross, which marks the location of the first Christian mission settlement in New Zealand, and the spot Samuel Marsden preached the first Christian service, on 25 December, 1814.

As summer gives way to autumn in the Northern Hemisphere—and soon winter—so various externalities that frame the work of boards and enduring performance of companies continue to press in. Topical externalities include climatic change; shifting geo-political forces; technological disruptions; diversity, equity and inclusion demands; ever-increasing levels of regulation; the emergence of ESG; and, stakeholder capitalism. The challenge for all directors and boards, whether they acknowledge it or not (or even notice or care!), is to respond well in the face of what is patently a dynamic environment—to ensure the fiduciary duty they accepted when agreeing to serve as a director is fulfilled. Steerage and guidance—the essence of corporate governance—requires every director, and the board collectively, to be alert, to both set a course and to respond well in the face of externalities. The mind’s eye needs to be looking ahead, to ensure the reason for the journey remains clear, and that decisions are made in the context of advancing towards the objective. Quite how that should be achieved is the underlying question that has driven my life’s work. Following an extended break from writing—a consequence of dealing with the passing of our patriarch—I have ‘arrived’ back at my desk to think and write again, about organisational performance, governance, strategy and the craft of board work. If you have a question, or would like to learn more about a particular aspect of board work or the impact boards can have on organisational performance, please let me know! If we are to journey far, we need to explore relevant topics and learn together.

As a devotee of life-long learning and a student of history, I keep an eye out for ideas and examples to share with boards and directors—in the hope that some might prove useful to help boards lead more effectively, from the boardroom. Amongst the news feeds and magazines that cross my desk (actually, computer screen), this journal often contains thought provoking articles. Recently, I was looking through some older issues and stumbled across this item, which explores effective leadership. The author offers seven 'keys' to effective leadership, as follows (I've taken the liberty of attaching a comment to each—a consideration for boards and directors):

Comments?

English can be a confusing language. The same word can have different meanings in different contexts (by 'bear', do you mean the animal, taking up arms, or putting up with someone; and is a 'ruler' a measuring instrument or a monarch?). Meaning and usage matters; more so because it is not static. Language evolves, whether by design or in response to an evolutionary development. Some refinements improve our ability to communicate effectively, others to defy logic. The understanding and usage of the terms 'governance' and 'corporate governance' are topical cases in point. While the term 'governance' is derived from the Greek root kybernetes meaning to steer, to guide, to pilot (typically a ship), a plethora of usages have emerged over time. Today, many different usages have become commonplace. These include the oversight of managers and what they do; the activities of the board; and the framework within which shareholders exert control and boards operate. It is also used to describe the board itself ("we'll need to get the governance to make that decision"). The term has also been applied in an even broader context, the business ecosystem (i.e., system of governance). The most extreme example I have heard is, "Governance can mean almost anything, it is completely idiosyncratic; different for every organisation". Things are made worse when two related but distinct concepts are conflated. Consider the definition of corporate governance and the practice of corporate governance. The former is relatively stable. Eells (1960) coined the term, to describe the structure and functioning of the corporate polity (the board). Later, Sir Adrian Cadbury (1992) added that 'corporate governance' is "the means by which companies are directed and controlled". The fundamental principle here is that corporate governance is a descriptor—the activity of the board. Compare that with the practice of corporate governance--how a board enacts corporate governance when it is in session. The means by which boards consider information and make decisions can and must be fluid depending on the situation at the time. The wider context merits a brief comment—the rules under which companies and their boards operate (statutes, codes and regulations), and the consequential impact of the board's decisions. These are necessary, because they define the wider environment; what is allowed and what is not. In recent years, I've heard many people include regulations and codes within their understanding of corporate governance. Similarly with the consequential impact of the board's decisions beyond the boardroom. Are either of these corporate governance? If you'll allow a sporting analogy, it's important to distinguish between the rules of the game, the game as played, and the final score. All are necessary, but only one is the game. To embrace an all-encompassing understanding suggests that corporate governance is ubiquitous, extending across the entirety of the company's operations and the functions of management, leadership and operations—not to mention the wider system of rules of regulations. This, I am convinced, takes us close to the root of the confusion that besets many directors. Every time I'm asked, I invoke Eells and Cadbury. A framework of laws and regulations is necessary, for these define the operating boundaries. But they are not corporate governance. In asserting that corporate governance is the means by which companies are directed and controlled, Cadbury was saying that corporate governance is the descriptor for the work of the board. And work, straightforwardly, is something to be practiced. Let's not lose sight of these distinctions. The continued 'sloppy' use of language serves only one purpose: to obfuscate.

|

SearchMusingsThoughts on corporate governance, strategy and boardcraft; our place in the world; and other topics that catch my attention. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

|

Dr. Peter Crow, CMInstD

|

© Copyright 2001-2024 | Terms of use & privacy

|