|

I have just arrived back in New Zealand, from ten days in the UK and Europe. My meetings with directors, advisors, academics, students and directors’ institutions had two primary objectives: to listen and to share. The listening aspect was to gain firsthand knowledge of issues and opportunities; the sharing aspect to provide updates on the craft of board work and my experiences as a practicing director. Learnings (a few immediate observations, in no particular order):

Amongst it all, there were some gems:

Several followup visits are now being planned, to advise, assess, educate and speak on topical board and organisational performance matters. If you want to discuss a matter of interest, or check my availability to assist, contact me for a confidential, obligation-free discussion. The headline picture, showing a derelict property in Soho, London, is analogous to the state of governance in many places in Europe: structurally sound but outwardly messy.

0 Comments

News of a new variant of the coronavirus emerged this week. B.1.1.529 (now Omicron, a moniker assigned by the World Health Organization) was first isolated by scientists in South Africa. Already, it has been detected in several neighbouring countries and in the United Kingdom, Belgium, Czechia, Hong Kong, Germany, Australia and Israel. Governments are reportedly “scrambling to protect their citizens from a potential outbreak". These responses are supposedly to protect but also, undoubtedly, to buy time. Given the experiences since the coronavirus disease was first detected and subsequently declared to be a global pandemic, the reactions to the latest variant are hardly surprising. News agencies and social media commentators have been up to their usual antics; newsfeeds are abuzz. Fear is a powerful catalyst, of course. But reliable guidance to indicate whether Omicron is more or less contagious, and more or less virulent, is yet to emerge. For example, the two cases in Australia are asymptomatic and both people are fully vaccinated. A calm response is needed. Another interesting aspect of the current situation is the response to those who first alerted the world to what they had discovered. When virologists in South Africa openly shared the results of their advanced gene sequencing tests, others (especially in so-called advanced economies) were quick to point the finger. They accused several countries in southern Africa of being the source of the outbreak, and ostracised them by banning travel—even from countries with no recorded cases—demonstrating the blame game is alive and well. Effective leaders (boards) do not get caught up in the blame game. They take another path:

Then, having prepared and decided upon a course of action, effective boards remain engaged. They keep their eyes open, scanning for weak signals that might portend danger. If danger strikes, they engage immediately and fully—supporting the executive response but remaining calm at all times. Is your board well-equipped to lead in an event that threatens the company’s prosperity or viability? And what is the likelihood it will oversee an appropriate response? Will it work calmly with the executives as a conjoint team to assess the situation and activate an appropriate response, or will it remain aloof and descend into finger pointing (perhaps because directors are more interested in protecting their personal reputation)? If there is any chance of the latter, consideration should be given to replacing the board with directors who are prepared to take their duties more seriously.

I arrived in London yesterday, ahead of what promises to be an interesting week. Formal commitments include delivery of the CBiS seminar in Coventry; planning for a future board research initiative; and a miscellany of meetings in which corporate governance, effective board practice and this recent article will be discussed. Two recent events, Carillion's fall from grace, and the now-public machinations at the Institute of Directors (which have resulted in the resignations of the chairman, Lady Barbara Judge, and deputy, Ken Olisa), are likely to invigorate discussions. Already, I've been asked to comment publicly on the Institute's troubles. The problems at the Institute of Directors in particular are troubling. They strike at the heart of what many say is wrong with boards and corporate governance; the Institute becoming a laughing stock in some quarters. The Institute's effectiveness as a professional body is contingent on it being the epitome of good board practice. The IoD chief executive, Stephen Martin, said on Friday that the resignations are a victory for good governance. They are not. Rather, they are an indictment of poor governance. Sadly, the Carillion and Institute of Directors cases are not unique. They are but two of many examples of poor practice that reinforce perceptions that boards are not effective. The ancient Chinese saying (more correctly, curse) seems especially applicable just now. If trust and confidence is to be restored, the power games, hubris and ineptitude apparent in some boardrooms need to be rectified. Flawed understandings of what corporate governance is and how it should be practiced also need to be corrected, especially the misguided belief that any particular board structure or composition is a reliable predictor of firm performance (the following letter highlights the conventional wisdom problem). The scene is set for some fascinating discussions this week. I'll let you know how I get on.

The 14th edition of the Corporate Governance Workshop convened by the European Institute of Advanced Studies in Management (EIASM) was held in Brussels, Belgium this week. A summary of the key insights from the first day follows below (click here to read the day two summary).

Bob Tricker just did it again. Long the doyen of corporate governance (Sir Adrian Cadbury used the term "father of corporate governance"), Tricker has just posted this article, a stinging critique of several emergent ideas that, through repetitive use, have permeated thinking and are becoming accepted as conventional wisdom. Risk, culture and diversity are singled out as populist memes. Yet robust evidence to support the notion that any of these memes are directly contributory to effective governance—let alone company performance—in any predictable manner is yet to emerge. Tricker's timing is, once again, exemplary. Thankfully, Tricker offers far more than a straightforward critique. He reminds readers that the purpose of the board of directors is to govern: The governance of a company includes overseeing the formulation of its strategy and policy making, supervision of executive performance, and ensuring corporate accountability. To create wealth, by providing employment, offering opportunities to suppliers, satisfying customers , and meeting shareholders' expectations. In calling out this matter, Tricker has hit the nail on the head—the effect of which is to place those motivated by the promulgation of unfounded memes in a rather awkward position. I am with Tricker; our understanding of corporate governance needs to be reset. Rather than pursue new memes (a perfectly adequate definition was established over fifty years ago), boards need to discover how to practice corporate governance effectively. Tricker (Corporate governance: Principles, policies and practices), Garratt (The fish rots from the head) and a few others provide excellent guidance as to how this might be achieved. (Disclosure: The two books named in this article are the ones that I refer to most often when working with boards. I commend them to you.)

Guest blog: Dr James Lockhart (College of Business, Massey University, New Zealand) During the late 1990s and early 2000s the hot topic in corporate governance was independent directors. Independent directors, it was proposed at the time, were the very panacea for performance improvement. It didn't really matter what the problem was the solution was independent directors, preferably a majority of them—and fast! Much effort went into defining an independent director and veritable lists emerged of the much needed characteristics and attributes, especially concerning ownership (the lack thereof); earnings from ownership (the lack thereof); or, employment or former employment (the lack thereof). Sadly, in all that enthusiasm the single most important attribute—independence of thought—was seldom mentioned. Fast forward a decade: now its diversity’s turn. Diversity, it is now proposed, is the panacea for improvement. Just like independent directors in the past (where no systemic evidence emerged supporting the assumption that independent directors actually improve performance) business is besieged with the idea that diversity on boards will enhance performance. All of the board diversity research conducted to date has been from outside the boardroom. We know that because there have been only four longitudinal studies conducted within the boardroom—one in Norway by Morton Huse; one by a serving board member (no conflicts there); one by a British colleague (Silke Machold); and, one by Peter Crow. So what is being measured? Just like the independent director research, the diversity research has reduced the boardroom to a simple input-output model. Diversity then refers to the measurable appearance of directors, such as, skin colour, ethnicity, sex, age, qualifications, professional backgrounds, and so on with a focus on sex, colour and age. But does diversity of appearance produce a diversity of opinion? Does diversity of appearance produce different strategic decisions that would not have been considered or not approved in the absence of such diversity on boards? Given that we don't know how effective men are in the boardroom, it is implausible to argue that we know the effectiveness of women. That is not to suggest we don't need more women on boards—we do. But the focus of the discussion ought to be one of building better boards, boards that are focused on wealth creation, and boards that deliver the company’s aspirations. As with the independent director argument that preceded it, repetition seems to matter—if something is repeated often enough it will eventually be believed. The discussion is being fuelled by the post-modern/neo-Marxist views currently dominating the B-school landscape, one that will acknowledge diversity everywhere other than amongst Caucasians. And with that, the point is lost. The focus of corporate governance should be on performance, in organisations where the thinking folder is overflowing, not what people look like. About Dr James Lockhart:

James is a Senior Lecturer at Massey University’s Business School, and a credentialed and practising company director. He teaches and researches in strategic management and corporate governance, and is responsible for the delivery of the College’s business internship and professional practice (Management) courses. He currently holds two directorships; is on the Defence Employers Support Council; and, is a Chartered Member of the Institute of Directors in New Zealand. Just over twelve months ago (6 January 2016 to be exact), I wrote this muse, a reflection on both the state of corporate governance and the usage of the term. At that time, confusion over the use of the term 'corporate governance' was common, and the profession of director was shadowed somewhat by several high profile failures and missteps. The blog post seemed to hit a nerve, triggering tens of thousands of page views and searches within Musings; many hundreds of comments, questions, debates and challenges (including some from people who took personal offence that the questions were even asked); and, speaking requests from around the world. That many people were asking whether corporate governance had hit troubled waters and were searching for answers to improve board effectiveness was reassuring. That was twelve months ago. How much progress has been made since? At the macro level, seismic geo-political decisions; the rise of populism and the diversity agenda; and, risks of many types, especially terrorism and cyber-risk have altered the landscape. Also, new governance codes and regulations have been introduced to provide boundaries and guidance to boards. Yet amongst the changing landscape something has remained remarkably constant: the list of corporate failures or significant missteps emanating, seemingly, from the boardroom continues to grow unabated. Wynyard Group and Wells Fargo are two recent additions; there are many others. Sadly, companies and their boards continue to fail despite good practice recommendations in the form of governance codes and (supposedly) increasing levels of awareness of what constitutes good practice. This is a serious problem: it suggests that, despite the best efforts of many, progress has been limited. Clearly, ideas and recommendations are not in short supply, but what of their efficacy—do they address root causes or only the symptoms? And what of the behaviours and motivations of directors themselves, and the board's commitment to value creation (cf. value protection or, worse still, reputation protection)? That the business landscape is and will continue to be both complex and ever-changing is axiomatic. If progress is to be made, shareholders need to see tangible results (a reasonable expectation, don't you think?), for which the board is responsible. If the board is to provide effective steerage and guidance, it needs to be discerning, pursuing good governance practices over spurious recommendations that address symptoms or populist ideals. How might this be achieved? An important priority for boards embarking on this journey towards effectiveness and good governance is to reach agreement on terminology, culture, the purpose of the company and the board's role in achieving the agreed purpose. If agreement can be reached, at least then the board will have a solid foundation upon which to assess options, make strategic decisions and, ultimately, pursue performance.

After initially standing strong, sustained lobbying and public commentary seems to have had an affect on British Prime Minister, Theresa May. News has emerged that the PM has backed down on an earlier pledge to introduce 'employee directors'. This is an interesting development. The Institute of Directors and unions (understandably) were supportive of the proposal. However, many business leaders expressed wonderment. Corporate governance has entered troubled waters, without question. But to suggest or even believe that structural changes might lead to better outcomes, without considering the function of boards holistically is short-sighted, at best—regardless of what any enquiry might determine. But let us not pre-empt the process now underway. The political process owes as much, to its constituency and, more generally, to the British economy. What do you think?

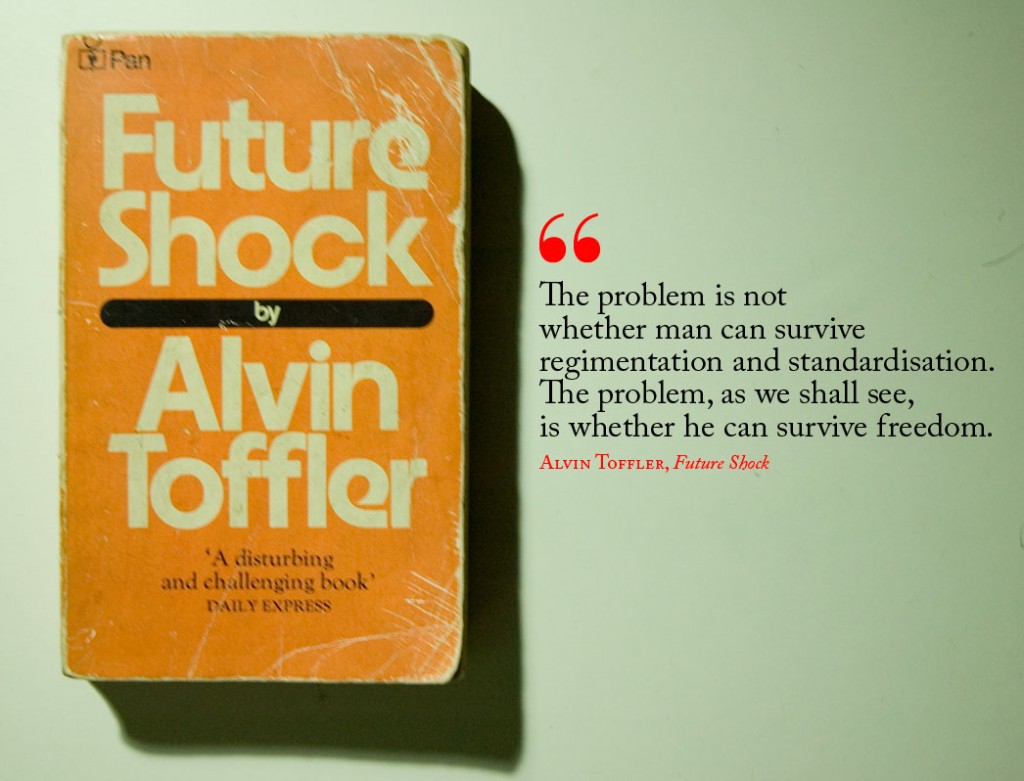

In 1970, Alvin Toffler's book Future Shock was published. It quickly became a bestseller. Toffler died recently, triggering a series of articles and reflections (including this one published in the New York Times) about his life and 'the book'. Toffler had an amazing ability to look well ahead of almost all of us, to think critically, and to make some sense of it all. Consider these observations by Manjoo in his reflection: Alvin Toffler ... warned that the accelerating pace of technological change would soon make us all sick. Yet in rereading Mr. Toffler’s book, as I did last week, it seems clear that his diagnosis has largely panned out, with local and global crises arising daily from our collective inability to deal with ever-faster change. That societies are racing with great speed to embrace new ideas and innovations, yet without the ability to cope with the consequences of high rates of change, might be one of the great problems of our age. Perhaps those in influential positions in society have a responsibility to shift their gaze, from their own ambitions towards altruistic ideas that serve the greater good? This is by no means a call to embrace utopian principles nor uniformity because we are all different. Much pragmatism is needed if society is to continue to endure. Leaders—of all types but especially business leaders, company directors, politicians and academics—could do well by (re)reading Future Shock. We need to talk about stuff, because we all have much to learn.

Recently, I had the privilege of addressing several groups of directors and executives in Brisbane, Australia on the topic of emerging governance trends. Over 200 directors of family and privately-held companies attended breakfast and dinner events hosted by TCB Solutions, Hanrick Curran and AMPLiFi Governance. The talks and the panel discussion that followed provided a candid summary of some of the challenges boards face and offered suggestions to guide boards intent on achieving high performance and good returns to shareholders. The dinner event was recorded. Clips of my talk (in two parts) and the panel discussion (in three parts) that followed are now available: If you have a question or a comment arising from these clips, or want to discuss the possibility of me speaking at an event or sharing ideas directly with your board, please get in touch. I'd be delighted to hear from you.

|

SearchMusingsThoughts on corporate governance, strategy and boardcraft; our place in the world; and other topics that catch my attention. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

|

Dr. Peter Crow, CMInstD

|

© Copyright 2001-2024 | Terms of use & privacy

|