|

The much-storied scandals at FIFA, HSBC and Toshiba have highlighted a plethora of weaknesses in the way large companies are led and run. Fingers have been pointed and blame apportioned. Management has copped a fair bit of flak, but the board has not been immune either. While the media has had a field day, finger pointing and broad statements provide little comfort to those in pursuit of long-term performance. Remedies are required. Reputability has studied a number of failures recently(*), in pursuit of remedies. The analysis identified nine prominent categories of weakness, the first six of which were influential in the majority of failures:

When these factors are considered holistically, the stark implication is that failure appears to be associated with board weakness in at least three areas (engagement, strategy and risk). If boards are to make effective contributions, these weaknesses need to be resolved. And therein lies a challenge: a return to first principles, and a different conception of corporate governance is likely to be necessary. Will boards embrace such a change in pursuit of better business performance? Let's hope so. (*) The full Reputability Report, entitled Deconstructing failure—Insights for boards, is available here.

0 Comments

The now very public overstatement of profits at Toshiba (approximately US$1.22bn over six years) has led to the downfall of the chief executive, Mr Hisao Tanaka (below), and seven other senior managers, all of whom were also board directors. The share price has taken a 25 per cent hit and the company's reputation is in tatters. What a mess. At least there is a modicum of accountability and remorse, something sadly lacking in many other cases including HSBC and Lombard Finance. Thankfully, people have begun thinking about what needs to change. So far, the response has followed a predictable course: The possibility of appointing independent directors to replace the disgraced directors has been mooted. Will this structural response be enough to fix the problem? Maybe, but I'm not convinced. Compliance responses rarely lead to sustainable change. (The compelling case is Sarbanes–Oxley: created post-Enron, it did little to prevent the GFC.) The problem seems to be more fundamental. The contemporary conception of corporate governance seems to be flawed. Consider these statements, which highlight the problem: The Japanese finance minister, Taro Aso, said: “If [Japan] fails to implement appropriate corporate governance, it could lose the market’s trust. It’s very regrettable.” (Guardian) The Toshiba scandal has raised questions about efforts by the Japanese government to improve corporate governance and culture. (NY Times) These seemingly innocuous statements are telling: Fix the compliance and the problem will be fixed. Yet history (Olympus, HSBC, FIFA, amongst many others) shows otherwise. Neither the 'monitor and comply' conception of corporate governance, nor the 'advise and monitor' variant espoused by many corporate governance codes and directors' institutes have achieved the desired outcomes. Yet, many boards dogmatically pursue such conceptions. How many more failures will it take to realise that additional layers of regulation and compliance-oriented boards that operate as policemen don't actually add value? How many more failures will it take to acknowledge that a new understanding of corporate governance and appropriate board practice might be appropriate? Emerging research seems to suggest that when boards adopt a strategic orientation, and corporate governance is re-conceived as a value-creating mechanism, increased performance is not only possible—it is potentially sustainable. Please get in touch if you'd like to know more.

Calls in support of appointing women as corporate directors have proliferated in recent years: the stated view being that the presence of women around the board table can improve decision quality and, potentially, business performance. Some legislatures have supported these calls by implementing quota systems. Many (but certainly not all) boards now count at least one female amongst their number. Anecdotal commentaries suggest that the level of attendance, engagement and discussion quality improves after a woman is appointed to a board. This is good, but another question lurks around the corner: If one capable women makes an impact and two more so, is an all-female board better still—or can we have too much of a good thing? Might an all-female board be as problematic as a board comprised only of men? I've seen some great all-male boards, some great all-female boards and, sadly, some rather ineffective diverse boards in action. That a diverse range of options are explored, independence of thought is displayed and that directors make considered decisions seem to be more important considerations than the physical composition of the board. Thankfully, the rhetoric is starting to mature along these lines. Hopefully director selection processes will soon follow, such that the qualities possessed by directors and the way they work together in the boardroom are the main considerations. Then, the gender (or any other diversity attribute) of directors should matter no more. Might this offer a viable path forward?

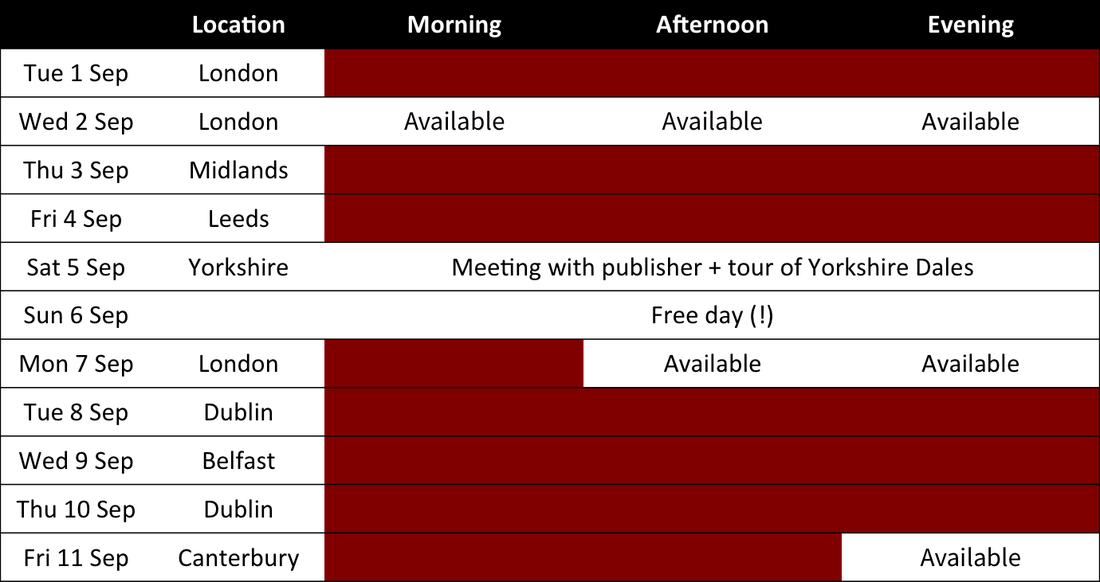

Wow, that was quick! Six days ago, plans for my Spring speaking and advisory tour to the UK and Ireland were 'starting to come together'. Now the eleven-day tour—to discuss corporate governance, value creation and board practice topics—is nearly full subscribed. Thank you! Three masterclasses, four 'general' speaking engagements, a masters-level lecture and several private meetings are confirmed on the programme. (Details of the 'public' events will be published by the event sponsors in due course.) In addition, two parties have requested planning meetings to discuss future advisory or speaking engagements, to occur in early 2016. If you think you might want to book me but want to talk about it first, that's entirely fine. Just let me know. As of today, just one full day (2 Sep) and one part-day (7 Sep) remain available to be booked. I'll be in London on both days as you can see. If you are based in London (or the home counties) and you want to book a meeting or speaking engagement, please get in touch soon--before it's too late!

How valuable is a board of directors to the performance of the business it governs? Does it influence business performance; or does it act as a policeman, "simply" monitoring the chief executive; and, do we even know? Many have attempted to answer this question. More often than not, the responses have been based on statistical analyses of secondary data (surveys, questionnaires, public data). Descriptions of what actually occurs in the boardroom typically remain hidden. Insights from direct observations of boards in action or from first-hand interviews are rare, so it pays to take note when they become available—as occurred when Nigel Bamford, chief executive of fireplace manufacturer Escea went on record this week. His comments, reported here, provide some interesting insights for boards to consider:

Bamford's final comment is perhaps the most telling. "In time, a board is useful for all businesses of reasonable scale and ambition." Two important lessons emerge from it:

The Bamford interview provides a much-needed glimpse into the boardroom of a successful company. However, and thankfully, the Escea experience is not unique. The insights are consistent with emerging research about what boards need to do if they are to exert influence on business performance. Consequently, important questions for your own board to consider include:

The seemingly innocuous statement, that business success is predicated on creating an effective strategy to achieve a goal, seems to have a fairly broad following amongst company leaders and directors. However, the reality (of what is needed to achieve business success) is somewhat different, as Ken Favaro points out here. Favaro's commentary is helpful, but only to a point. His suggestion that a 'big idea' is necessary to success is not particularly reassuring. What of all the other successful companies out there? How did they succeed if they didn't have a singular 'big idea', or even several 'medium ideas' for that matter? There's got to be something else that drives success. The consistent theme that I've observed amongst companies that have enjoyed long-term success is that they have had a clear sense of why they exist—a purpose. This is because people get behind causes, not things. Sinek's 'golden circles' thesis is the best annunciation of this that I have seen. Boards and management teams grappling with strategy and the future of their business should watch Sinek and use his ideas to re-think their business. Those that do so have told me it's the best 18 minutes they have invested for a long time, far better than any search for a 'big idea'.

What is it with the women on boards and diversity discourse? These topics, both arguably proxies for the on-going fight for a more equal society, have been the subjects of much research and discussion over the last decade or more. Claims and counter-claims have been asserted—sometimes quite stridently—in both the popular press and in the academic literature. While many commentators have asserted that the presence of women in boardrooms, or diversity amongst directors is causal to increased company performance (and others have jumped on the bandwagon), a small number of bold souls have questioned the analysis, recognising that any linkage is complex and likely to be contextual. Now, Caroline Turner, a leading commentator appears to have called time on the rather simplistic assertions that have dominated the discourse (click here to read her recent article). Her response to the question of whether gender diversity is good, bad or indifferent is "It depends on which study you read". I agree. Importantly, Turner's conclusion (that "solid research by highly respected organizations, disputed by some, shows a correlation between gender diversity and results") and appeal (for more research) signals a much needed maturing of the rhetoric. Researchers, consultants and commentators need to build on Turner's comments. If we are to understand how boards work, and how influence is exerted, boards need to be observed in action. Sophisticated analyses, capable of exposing factors that may not be directly observable or consistently applicable, are also required. The resolution of the problem (of explaining how boards influence business performance) is more likely to be found in the subtleties of director qualities and behaviours, and the complexities of how they work together, than in any regular correlation between an observable attribute and subsequent business performance. Thank you Caroline Turner for recognising this, and for advancing the conversation.

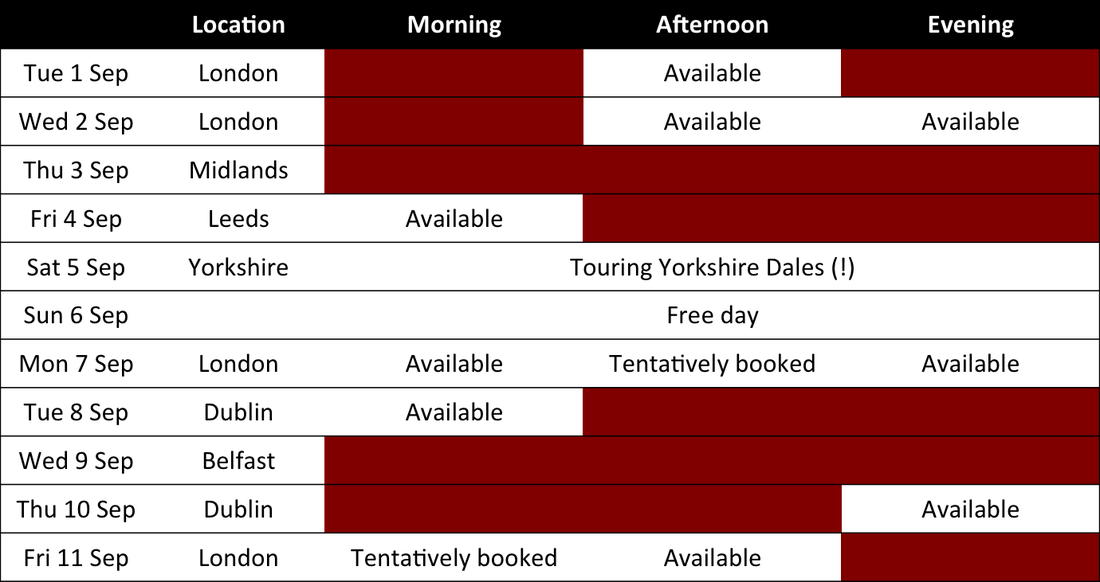

Plans for my next trip to Great Britain and Ireland—a speaking and advisory tour to share insights from my latest research and practical experience in boardrooms—are starting to come together. My schedule is filling up—only a third of the available slots are still available. Thank you to everyone who has already reserved space. The dates and times you have requested are secure. If you are based in London (or the home counties), Leeds (or elsewhere in Yorkshire) or Dublin; and you want me to address your board or executive team, discuss a future speaking or advisory engagement, or chat privately about a difficult challenge, please get in touch soon to avoid disappointment. I look forward to hearing from you, and then to discussing any aspect of board practice, corporate governance, strategic management, value creation or business performance that is of interest to you.

The demarcation between the responsibilities of directors and promoters and those of shareholders was made plain in the Hanover Finance case today. The Financial Markets Authority filed a civil suit against six named parties (five directors and one shareholder), following the collapse of the business several years ago, and a decision by the Serious Fraud Office to abandon criminal charges. The FMA has been pursuing the parties for a couple of years. Now, today, an $18M out of court settlement has been announced. However, there is a catch. Five of the six parties (the directors, excluding the named shareholder) were named. The sixth party, well-known businessman Eric Watson, refused to admit he was a promoter of the company (as claimed by the FMA). Consequently, he has avoided being named as a party to the settlement. Thus, the decision demonstrates the distinction between the responsibilities of directors (to make decisions and bear consequences) and those of shareholders (liability is limited to loss of equity). One final point. The response of the directors was interesting, to say the least. The directors continue to deny any liability for wrong-doing—even though they agreed to the settlement. Huh? A company has failed. The directors knowingly made major decisions including the issuance of prospectus documentation and they promoted the prospectus. Agreement to settle (funded by insurers, no doubt) implies culpability at some level you would think. Yet liability is denied. Doesn't that sound a bit odd?

Every now and again a thought piece really sets me thinking—like this one, which arrived in a mail feed over the weekend: Most people like the comfort of having rules to follow. Rules give us a clear understanding of what is expected. Obey the rules and we feel safe, confident in our actions, and assured of positive outcomes. However, excessive focus on rules can make us arrogant and judgmental. Hard law (that is, statutes and compliance codes) seems to be the de rigueur response to major corporate indiscretion. Sarbanes–Oxley, Dodd–Frank and the UK Corporate Governance Code are but three recent examples. These measures set fairly well defined expectations in terms of how boards are supposed to operate. However, they don't ensure performance. They add cost as (most) companies seek to conform, or they lead to evasive practice). Might the strong focus on regulation, statutes and compliance codes actually be bad for business performance and economic growth, especially as most directors and boards operate ethically and well within accepted social and societal norms? How might the risk–cost balance change if there were fewer rules to divert directors' attention away from value creation?

|

SearchMusingsThoughts on corporate governance, strategy and boardcraft; our place in the world; and other topics that catch my attention. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

|

Dr. Peter Crow, CMInstD

|

© Copyright 2001-2024 | Terms of use & privacy

|