|

I'm writing to express gratitude for your interest in my upcoming talk at the British Academy of Management conference. That my research to explain how boards can influence the achievement of company performance outcomes has stimulated such interest, even before it is completed, has amazed me. Thank you.

My paper will be on presented on Thu 11 September. A copy will be posted here afterwards. If you are planning to attend the conference and would like to meet between sessions, over lunch or in the evening, please contact me via Twitter or email. Also, I'll post summaries and reflections on this blog throughout the BAM conference, to give those that cannot attend an insight into what was discussed. To those people that have asked questions about my research: I will send a private reply. To those that have asked about meetings and speaking engagements in London and elsewhere: my schedule is now full (sorry!). However, I will be back in the UK and Europe in November. If you'd like to meet me then, please contact me to make an arrangement.

0 Comments

In seven days time, I expect to be at least 35,000ft above the north-west reaches of the UK, nearing the end of a journey from Auckland, New Zealand to London, England. The reason for my trip? I'm booked to speak at the British Academy of Management conference in Belfast. While in the UK, I'll also attend some meetings, and take a few days off with my wife who is travelling with me. The trip involves 40,000km of air travel; 24 hours of timezone change; and, a season change (from late winter to late summer and back).

On the surface, it'll be a demanding trip. However, the trip may actually be a blessing in disguise: a time of relative calm sandwiched between two even busier periods. Here's what I've been up to in recent weeks:

A new list of actions to be completed before Christmas awaits my attention when I get home:

Measured against these lists, the seemingly hectic trip, to fulfil a speaking engagement and attend meetings on the other side of the planet, might not be so demanding after all. In fact, the trip may be analogous to the eye of storm. My point? The here-and-now can seem pretty hectic. Long-distance travel can be pretty demanding. However, if one steps back and looks at the big picture, periods of relative calm become visible amongst the busyness. Seek them out and enjoy them, for the next period of busyness lies in wait. Bryan Gaynor shone the light on a very important problem today—that many large firms in New Zealand simply are not growing in line with the growth of the economy. In other words, they are going backwards. Gaynor's analysis is insightful: to lose ground when the flow is good suggests that something is amiss. This raises several important follow-on questions:

While the issues before each firm will be unique, there are some constants:

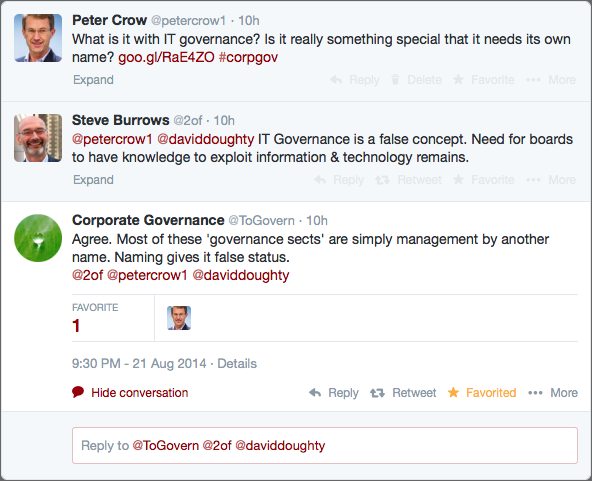

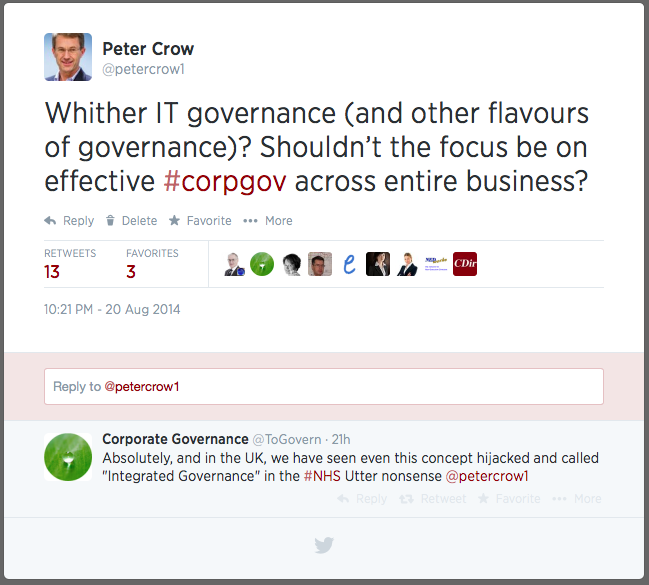

Hopefully, the boards of these firms will take stock, ask some quite tough questions, and make appropriate adjustments to get back on track. High company performance has many positive flow-on benefits beyond shareholder wealth, and these need to be realised if at all possible. The English language is constantly evolving, as we find new ways of describing things and expressing ourselves. Sometimes, words and phrases are helpful abbreviations of a new social phenomena ('selfie'). Other words and phrases convey a reasonably strong value judgement, like the one I learnt today: The use of 'sect' to describe those that promote new ideas about boards and corporate governance, or suggest derivations or deviations from existing ideas, raises the stakes. According to my dictionary a sect is "a group of people with somewhat different religious beliefs (typically regarded as heretical) from those of a larger group to which they belong".

Why some people find it necessary to promote aspects of the bigger picture as being the picture is beyond me. If the purpose of a board is to optimise company performance in accordance with the shareholder's wishes, and corporate governance is the mechanism through which the board seeks to achieve this, is this not where our effort should lie? I got a bit frustrated yesterday. Three messages arrived from people promoting IT governance—heavily. The problem wasn't so much the topic per se, but rather the brow-beating that accompanied it. According to the messages, companies need IT governance, and it is important for CIOs to be appointed to boards. Really? The board's responsibility is to think about the company as a whole—to set strategy; to make decisions; and, to monitor strategy implementation to ensure goals are achieved. I couldn't find a credible explanation as to why IT governance was crucial, so decided to ask the question: To my surprise, the question was retweeted to tens of thousands of others. Several influential people replied privately to say they were puzzled. @ToGovern replied publicly, as you can see. As I've thought about it some more, I've found myself wondering why people find it necessary to grab concepts, re-name them and re-apply them, often inappropriately. For example:

The board's interest in the first example is verification, and strategic decision–making in the second—both of which are important parts of the corporate governance remit. The information feeds to inform these matters are just that, information feeds. If IT professionals want boards to understand what they do; what they want to do; and, what the emerging trends are, they need to think and speak like boards do. Proposals need to be in the context of approved strategy. Project and management reports both need to demonstrate progress towards agreed corporate goals. Market reports needs to demonstrate relevance to, or impact on, the corporate strategy. If managers write their board reports and provide information in this way, and advisors provide sound advice, directors should have no problem asking appropriate questions in order to understand the issues. If this happens, technology-related topics can be handled by boards in the same way as any other major agenda item, can't they? One of the big challenges of tackling a major project relates to vitality. When we set out to tackle something new, be it a hobby, a job, a long walk, a marriage or something other 'project'; we generally start with much hope and anticipation. However, over time, we can get a little stale, as the rigours and routines of the daily grind take precedence in our mind over the goal that we set out to achieve. Sound familiar?

Regular readers will know that I've been working on a major research project in early 2012. The good news is that the end is now in sight. However, there is still much to do and the risk of getting stale is never far away. One of the techniques that I have used to keep fresh is to change the focus temporarily—by helping others solve gnarly real-world problems. Today for example, I had the privilege of working with a group of directors and a manager—helping them wrestle with their business, to try to get some clarity around core purpose and strategic priorities. The Chair's closing comment, "the morning was incredibly worthwhile", suggested that progress had been made. Next week, I have an independent review of another board to do. That board has some interesting challenges around focus; role; and, interaction with the Chief Executive. Small 'side' projects keep me mentally fresh. They get me out of the office and away from the routine of the research. Sitting with real people, and helping them wrestle with real problems, is so invigorating. Crucially, when I return to the research, I feel sharper and seem to work more effectively. How do you freshen up? The Institute of Directors has just played a wonderful hand, and in so doing may have started an important transition—from being perceived as being a nice club for well-to-do directors, to being a forthright influencer in the commercial world. In recent years, most professional bodies seem to have concentrated their efforts on recruitment, membership services and education. Some, including the Institute of Directors in New Zealand, have established a chartered director programme, in an effort to raise the level of professionalism across the director community. However, one important element has been missing, or at least not apparent, until now: lobbying.

The Institute seems to have emerged from the shadows however, by taking this tough stance on executive remuneration. While the move may not win many friends amongst those who frequent the top echelons of corporate power, it signals a return to the principles of the royal charter under which the organisation was formed. It also signals intent: to hold directors accountable and, hopefully, to commence an active lobbying initiative. That standards of professionalism be raised, lawmakers be influenced and directors be held to account bodes well for shareholders seeking to wrest back control of the companies that they own. It also bodes well for the community, because high company performance is an important contributor to economic growth and societal well-being. Congratulations are due to the Institute. Simon Walker and his colleagues have made a bold move. Now we need to see more of this type of behaviour—from the Institute, and from the institutes in New Zealand, USA, Australia and elsewhere. For some months now, I have been wrestling with the possibility that corporate governance might not be a structure or a process, but rather a mechanism that is activated by boards in some way. I've been beavering away on this, without seeing much other research activity in the same area—until today, when this release from Penn State arrived. The article referred to corporate governance and mechanisms in the same sentence. Wow! Could this article point to some research along the same lines as my attempts to get to the bottom of what actually happens in boardrooms? Here's the first three paragraphs: UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- The most effective corporate governance occurs when a mix of complementary mechanisms that include CEO incentive alignment and both internal and external monitoring mechanisms are present, according to a new study from Penn State Smeal College of Business faculty member Vilmos Misangyi and his colleague from the Singapore Management University. By the time I got this far—three paragraphs into a nine paragraph release—the wind was gone from my sails. My hopes were dashed. Misangyi and Acharya seem to suggest that effective corporate governance occurs when CEO incentive alignment and monitoring mechanisms are in place. They evaluated two variables (they call them mechanisms) in 1500 firms and described their research as holistic. Interesting. There is a growing body of research that suggests that board's involvement in the development of strategy and in the making of decisions is what matters. Misangyi and Acharya's release makes no mention of anything along these lines, nor is there any suggestion that the researchers directly observed any of the 1500 boards in their study.

I'm looking forward to reading the full research report when it is published, to see whether this is another study based on secondary data and hypothetico-deductive science, or whether Misangyi and Acharya have discovered a whole new paradigm. Since Robin Williams' passing earlier this week, I've been pondering the gifted–troubled tension that many highly capable people struggle with. Williams was a gifted actor, yet he had a troubled private life. He wasn't unique in that regard: Alan Turing, John Nash (A Beautiful Mind) and many others were similarly afflicted.

As I pondered this, something dawned on me: many entrepreneurs face the same tension. They are great optimists, yet they often harbour a darker side. They have more ideas than most of us have hot breakfasts. However, many don't listen or take guidance well. They are happy in public, but some, privately, actually lack confidence and self-esteem. Consequently, the oversight of companies led by entrepreneurs can be a big challenge for boards: one of influence. How does a board get the most out of the entrepreneur, without suppressing their optimism? How about motivation? Zach Cutler's insightful summary, of five things that happy entrepreneurs take the time to do, provides a really good starting point for boards:

If boards can find ways of supporting these things that motivate entrepreneurs, then they may find it easier to focus their enthusiasm and optimism—onto the things that actually matter for the growth and development of the company, not just those things that grab the entrepreneur's attention today.  The steady stream of new listings on the New Zealand Stock Exchange in recent months has been fascinating to watch; the behaviours of the participants especially so. Stock markets are, by their very nature, bastions of capitalism; a central place for sellers and buyers to trade stocks in the pursuit of personal or corporate wealth. The New Zealand market is no exception. The New Zealand market is operated by NZX Limited, itself a publicly traded stock. Yesterday, when NZX reported its six-month result ($7m profit on $31.2m revenue), the CEO touted for more listings. This should not be surprising, as more participants means more revenues. High company performance is generally recognised as being good, because important economic and societal benefits flow from high company performance—as long as the profits stay in the system. Yet when one looks under the covers, a large portion of the profits being generated by NZX may actually be leaving the system. The largest NZX shareholder (39%) is New Zealand Central Securities Nominees Limited, a trading company owned by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand. This means nearly 40% of all dividends paid by NZX go to the government; they leave the system. Is this good? Rather than an exchange that generates large profits—much of which end up in the governments coffers—wouldn't the market be better served by one that operates on a cost-recovery basis, whereby all participants pay a recovery levy to play? Given NZX's inherent efficiency, fees could be reduced by 22% without difficulty. This would leave more money in the hands of the participating companies—where it is most needed to grow and develop the economy. Such an approach seems to be more conducive to capitalist ideals and, importantly, improved societal wellbeing don't you think? |

SearchMusingsThoughts on corporate governance, strategy and boardcraft; our place in the world; and other topics that catch my attention. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

|

Dr. Peter Crow, CMInstD

|

© Copyright 2001-2024 | Terms of use & privacy

|