|

The effectiveness of company boards has become a hot topic in recent years, especially as the general public has become aware of various failures, missteps, poor practice, hubris and ineptitude, but also as attention has increasingly moved from the chief executive to the boardroom in search of high company performance. The role of the company director is not for the faint-hearted. Market forces, technical innovations and human factors all contribute to a complex and dynamic operating environment. Directors need to consider and make sense of information from multiple sources, and make informed decisions in the best interests of the company. It goes without saying that directors and boards need to maintain a continuous learning mindset if they are to keep up to date and contribute effectively. In a few days, I'll be in Sydney, Australia (18–20 September), to work with directors committed to the ideal of high performance. While the main objective of the visit is to present the first day of a new three-day course entitled "The effective director", I have time available to attend other meetings to share ideas and discuss emerging trends in corporate governance, strategic management and related topics of interest. If you'd like to get together while I'm in Sydney, please let me know. I have some free time and would be delighted to meet informally over coffee, or in a boardroom setting with you and your director colleagues.

0 Comments

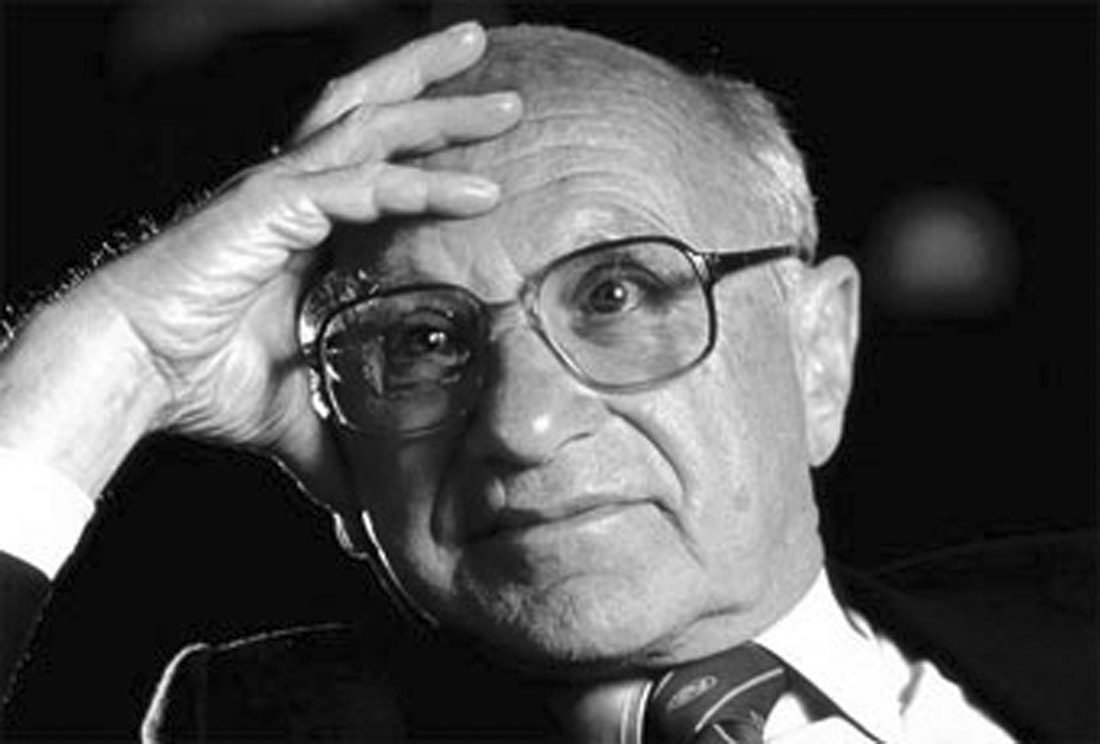

In September 1970, The New York Times Magazine published an article that subsequently became a catalyst, a touchpaper even, for a step change in the understanding of the purpose of business and, as a consequence, the priorities of managers and boards of directors. Milton Friedman, an economist and Nobel laureate, argued that the doctrine of 'shareholder primacy' should prevail over that of 'social responsibility'. The article garnered much attention (becoming seminal along the way) especially amongst those shareholders, directors and managers for whom the maximisation of profit was of primary (read: exclusive), interest. The statement most commonly used to justify the profit maximisation doctrine is right at the end of the article: "There is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase profits" Superficially, this statement is pretty clear: the purpose of business is profit and nothing else matters. But this statement is incomplete, a portion of a longer sentence. To stop reading at 'increase profits' is to read Friedman out of context. The complete sentence is as follows: "There is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in free and open competition without deception or fraud." Friedman was clear. He argued that the maximisation of profit is an important priority of companies, and he argued that this is not, and cannot be, an unbounded endeavour—much less an exclusive one. The proviso followed without as much as a comma—the pursuit of profit needs to occur within the context of prevailing law and regulation (rules of the game), competition and fair play. That Friedman's guidance was so clear begs a rather awkward question: Why has it been misinterpreted by so many shareholders and boards?

|

SearchMusingsThoughts on corporate governance, strategy and boardcraft; our place in the world; and other topics that catch my attention. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

|

Dr. Peter Crow, CMInstD

|

© Copyright 2001-2024 | Terms of use & privacy

|