|

The June solstice is almost upon us. Davos, the World Economic Forum's annual meeting of elite political, academic and business leaders (some would say, talkfest), is over for another year. Private jets have returned to base, and the thoughts of leaders (in the northern hemisphere, at least) are turning to summer holidays and, with it, relaxation, reading lists and an opportunity to cogitate. Meanwhile, leaders south of the equator press on, for the June solstice marks the onset of winter. Metaphorically, the June and December solstices are signposts: marker pegs that signal pending change. Over the past couple of years, I have been watching intently one signpost in particular, wondering whether it might portend a change in relation to board work, or whether it might be a mirage that can be ignored. ESG, a three-letter acronym for environmental, social and governance, was coined in 2005 by a group associated with the United Nations. The stated goal was to put pressure on companies to think beyond financial indicators as the primary indicator of business performance, and to report accordingly. A veritable industry of so-called experts (many self-styled) has emerged in recent years, all claiming to help businesses respond well to ESG demands and expectations. Many business leaders, activists, politicians and directors’ institutions have latched on too, themselves motivated by various self-interests. That interest in operating sustainably and improving reporting is high is no bad thing. However, to date, evidence to support the proposition that the embrace of ESG leads to better performance is yet to emerge. Indeed, cracks are starting to appear. Several critical thinkers have called out ESG as offering less than what has been claimed. Some have gone as far as asserting that ESG is a ‘solution’ looking for a problem (read: wasted effort). Whether it is or not remains to be seen. However, there is cause for concern: discussion has reached the point that advocates have deemed it necessary to make counter arguments, to defend ESG. That several different definitions of the term are circulating doesn't help. Boards also need to be very alert and ask probing questions, to ensure they continue to discharge their duties. In particular, boards need to assess whether ESG proposals are conducive to improved business performance, and if ESG is a harbinger of substantive change in the way businesses need to operate or yet one more TLA, a fad that will ultimately be consigned to the history books and, in time, forgotten. That questions are being asked—openly—should be a catalyst for political, civic and business leaders to check that the aspiration (claim), intention (strategy), actions taken and resultant outcomes are aligned. On the evidence to hand, ESG is unlikely to be a panacea. Thus, a level of scepticism in relation to the purported benefits of ESG is warranted.

0 Comments

The invisible hand, Adam Smith opined, is a metaphor for self-corrective power in systems. If one party within a system, or one part of a system, becomes too strong or dominant then, sooner or later, an alternative will emerge, to restore equilibrium. Regardless of whether it is applied personally (think: bodily effects of obesity), in politics (extreme ideologies), or at population (demographic and social inequities) or even planetary level (geological stresses), the maxim holds, it seems. In business, the self-corrective power is the market. If price is perceived to be too high, or too low; workplace culture or employment conditions are unhealthy; product or service quality does not meet expectations; or, return on funds invested is too low, prospective customers (staff, suppliers, shareholders) respond—they seek alternatives. This inherent power, held by those who interact within the system, has underpinned sustainable commerce for centuries, even millennia. And yet some governments and para-governmental agencies find it necessary to intervene, through the creation of rules. But such interventions are usually costly, and they rarely achieve enduring equilibrium. Inevitably, those with decision-making power within companies find ways around what they perceive to be unreasonable barriers to sustainable prosperity. Please don't misconstrue this observation as a wholesale rejection of rules. It is not. Rather, it is a plea for regulators and boards to take stock. What is the minimum regulatory or policy framework to facilitate commerce and ensure fairness; the point beyond which effort will naturally be diverted, resulting in inefficiencies? Consider stakeholder capitalism as a case in point. Advocates argue a more stringent regulatory framework is required to ensure the value created by companies is 'shared equitably'. This seems fair. But what if an external stakeholder group influences company strategy in a direction different from that which the board and management have agreed is appropriate? Where does accountability lie is such a situation? Should external stakeholder groups be held to account if they ‘force’ certain practices and policies onto a company that impair the performance of the business and lead to in value erosion? The more time spent satisficing the expectations of external stakeholders, including complying with regulatory requirements, the less time remains to pursue agreed goals and sustainable performance. If company leaders—boards in particular—focus resolutely on the pursuit of agreed strategy, and on the achievement and reporting of results across the three critical dimensions, namely, social (staff, client, supplier satisfaction, which includes fair pay, good relations, etc.); environmental (impact, minimising footprint) and economic (financial return to shareholders), prosperity should follow. But if leaders trade recklessly; abuse staff or suppliers, price goods and services above what is reasonable, or disregard the environment, the company they govern deserves to struggle or, in severe situations, fail. Regardless, the invisible hand will have made its presence felt. What more should anyone expect?

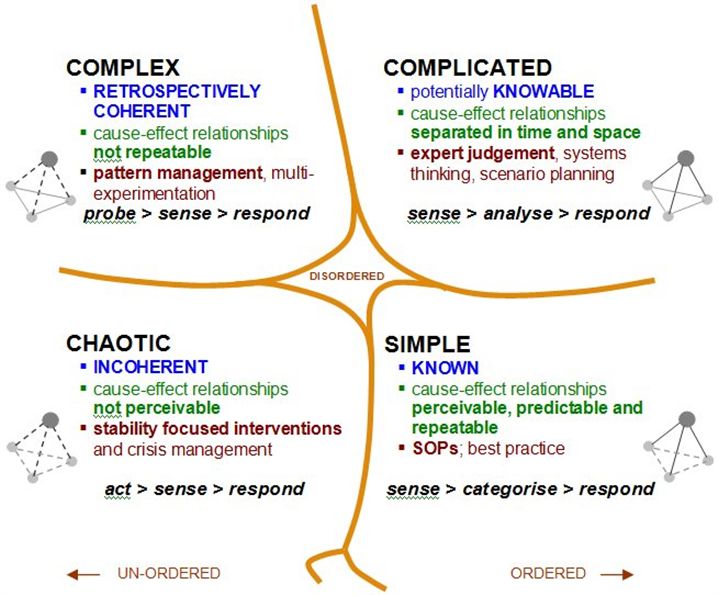

The global crisis brought about by COVID19 has precipitated a range of reactions and emotional responses. These have included fear (of catching the virus, becoming very sick or even losing life); frustration (that civil liberties have been withdrawn); anger (the prospect of high levels of state control after the immediate crisis has passed); praise (the selfless actions of first responders and healthcare professionals); disappointment (of not being able to spend time with loved ones); beatification (of some political leaders); confusion (about the conflicting official guidance); and more besides. Inherent biases are also on display, as people turn to social media to express themselves (or react to what others have written). Some have supported the government's actions and public health responses; others have been highly critical, even vitriolic. It's perfectly natural for people to react to what they read and hear about the situation and the uncertainty foisted upon them—and to be curious about the motivations of leaders and what the future might hold. In times of great crisis (when chaos tends to reign), the most important priority for a leader (board of directors, executive team, community leaders or the government) is to re-establish a sense of stability and order, noting the fine line between providing leadership and imposing one's will. Effective leaders tend to roll their sleeves up, identify options, openly encourage alternative perspectives, make decisions based on best-available data and assumptions thought valid at the time of the decision, and explain why decisions have been taken. But as the situation develops—and it will, both naturally and in response to various interventions—progress and data need to be reviewed. Effective leaders display an openness to reverse or amend earlier decisions promptly if new data do not conform to a priori assumptions. Transparency and accountability are both crucial to maintain the confidence and support of stakeholders. But effective leaders also look beyond the immediate crisis. They ask questions to discover what the future might hold, and whether the crisis presents an opportunity to do things differently. But they don't pursue change for change sake. Over the past two or three weeks, a bevy of visions of what a post-COVID19 world could or should look like have been published by think-tank groups; futurists; independent consultants; journalists; social media commentators; self-styled experts; company leaders and other pundits. Amongst those shared to date, 'digital transformation'; 'locking in new ways of working'; 'a post-office world'; 'the end of globalisation'; 'balanced capitalism'; 'a more inclusive society' and other similar phrases have featured prominently. Some of the proposals I have seen are coherent and merit further investigation; others are little more than bias-laden and thinly-veiled attempts to influence public opinion in favour the author's favoured ideology. Hopefully, political leaders have been considering options to rebuild the economy and social fabric too, but these are yet to be revealed. With so many options (and many more to come, no doubt), business, political and community leaders face a daunting challenge: of threshing the wheat from the chaff, and making strategically-important decisions in the best interests of others, not self. To decide where and how to move next, in the midst of great ambiguity and uncertainty, is not for the faint-hearted. Wisdom and maturity are invaluable capabilities in this context. Many tools and frameworks are now available to help leaders make sense of a multiplicity of options, and to respond well given the prevailing context. The Cynefin Framework is worthy of consideration. (Hat-tip to a Netherlands-based colleague who reminded me of it recently.) Regardless of which approach or framework you use, high-level sense-making and systems thinking expertise is vital. Heterodox perspectives are to be encouraged too. Without these, leaders run the risk of becoming introspective, leaning in on natural biases or, worse, preferred ideologies. Also, great care must be exercised to ensure intended visions are made plain, strategies are coherent and decisions are evidence-based. If such care is not taken, those concerned by what they deem to be inappropriate experimentation or investigation might bite back. Curiosity killed the cat, after all. The COVID19-induced crisis presents leaders (politicians, boards of directors, community leaders) with a golden opportunity to take stock and, having thought carefully, make decisions in the best interests of the constituency, company, community they serve. Effective decision-making in chaotic situations is far from straightforward, but our future prosperity depends on it.

Trust is one of those social building blocks that is crucial for getting things done with others. Board work by no means exempt. When directors a faced with making strategically-important decisions, they must rely on information from and interaction with their board colleagues, the chief executive and any other advisors who may have been invited to contribute. Then, after consideration and having made a decision, the board needs to follow through, by ensuring the decision is implemented well. But, and sadly, the levels of trust both between directors and with external stakeholder groups is often lower than what is needed for effective decision-making. The following comments, originally published in 2016 by EpsenFuller (subsequently acquired by ZRG Partners), make the point deftly: Board directors today face a variety of challenges. Whether it is a case of corruption or the increasing threat of cybercriminals, their performance in dealing with these issues is the subject of considerable attention, explained The Huffington Post (Jan. 25, Loeb). Investors, consumers and NGOs alike are looking to boards for accountability in terms of company performance. Yet, a recent study found that public trust in boards of directors is lower than that of CEOs. A mere 44 per cent of survey participants claimed to have trust in a company's board—five per cent less than trust in CEOs. Influential constituencies are demanding that boards perform at exceptional levels while maintaining distinct independence from company executives. That some directors do themselves no favours (through poor behaviour, malfeasance, hubris and failing to complete actions, for example) is self-evident. But all is not lost. High levels of performance are possible—if all of the directors commit to working together (both as a board and with management) and reach agreement on the company's core purpose; the strategy to be pursued to achieve the agreed purpose; how performance will be measured; and the values that will underpin behaviour standards, decisions, and everything the company does and stands for. Perhaps if more boards embraced this mindset (working together), with the company's best interests to the fore, the trust problem that generates so much tension (not to mention column inches) would gradually become a thing of the past. Is this expectation worth striving for, or do you think it is too ambitious?

The 2018 edition of the Global Peter Drucker Forum was convened in Vienna, Austria this week. This post summarises insights from the second day (click here for insights from Day 1). I didn't take as many notes on the second day, preferring instead to sit, listen and dwell on what was said. (I also missed a couple of sessions, one to finalise my own preparations to speak; another to spend time privately with a two inspirational thinkers.) However, there were, for me, two speakers that really stamped their mark on the day, as follows: Hermann Hauser, director of Amadeus Capital Partners and chair of the European Innovation Council, delivered a strong message, arguing that humanity is on the cusp of an inflection point (moving beyond evolution to design thinking) that has the potential to 'change everything' in the reasonably near future. He identified four significant disrupters:

The implications of these disrupters are, frankly, rather daunting. Synthetic biology offers the prospect of defeating disease, but at what cost? Quantum computing has the potential to render electronic security systems useless. One doesn't have to be a rocket scientist to realise the massive implications for commerce, banking and warfare. Researchers and technologists are committed to bringing these capabilities to market. But at what cost to humanity? The ethical implications are not insignificant. Recognising this, Hauser suggested that the state has an important role to play, to ensure appropriate regulatory boundaries and safeguards are established. But it must act quickly, before the genie gets out. Martin Wolf, chief economics editor of the Financial Times, spoke passionately about the role of the state; in his view, the single-most important institution in human history. I first heard Wolf speak a few years ago. He left a strong impression on me then, and did so again as he spoke. Addressing the question of how states can 'work better', Wolf named several important roles that the state 'must' fulfil par excellence:

Such roles need to be implemented with aplomb. Failure to do so will inevitably lead to anarchy, in Wolf's view.

When Theresa May went on record recently, the key message for boards was that they needed to pull their socks up lest additional structural measures including employee directors become a requirement for UK companies. Much of the commentary was aimed at the boards of publicly-listed companies, in an attempt to curb (perceived and real) corporate excess in the form of excessive remuneration; hubris; and, a flagrant disregard of some stakeholders. Today, ICSA: The Governance Institute announced that it had written to the Prime Minister calling for the boards of privately-held companies to be held to the same levels of accountability and disclosure as publicly-listed firms. This request seems perfectly reasonable, especially as the UK Companies Act 2006 applies to all companies. The UK statute is clear: directors (actually, boards because it is boards that make decisions) are required to consider the long-term consequences of their decisions and the impact on employees and the community. Good practice suggests that boards should, amongst the things, keep shareholders informed (through the board's annual report to shareholders) of its activities. ICSA is right to raise the issue, but will enforced compliance with codes of practice fix the problem? If boards act within the law and in accordance with codes of practice as they pursue business objectives, then letters such as the one written by ICSA should not be necessary. But they don't. Some directors and boards take liberties. Enough examples have come to light in recent years (e.g., HSBC, FIFA, Volkswagen, Fonterra, Solid Energy, Toshiba and, most recently, BHS) to suggest that some boards knowingly run close to or beyond boundaries defined in law. But where does the real problem lie? Is it with the law, the principles-based codes of practice; the directors themselves; or, something else entirely? Consider this: The road toll has not declined as a direct result of increased enforcement measures but rather a change of behaviour—drivers choosing to driver safer vehicles more carefully. Are boards any different? If boards are analogous to drivers, probably not. Unless and until boards make a conscious decision to embrace company performance as an important priority, and to do so in accordance with both established law and published codes of practice, I suspect the media will continue to be gainfully employed. Finally, shareholders have an important and oft overlooked contribution to make. Recent experience suggests that greater care is needed in the appointment process, to ensure only suitably capable directors who are intent on acting in the best interests of the company are appointed to boards. In addition, shareholders should not overlook their right to hold directors to account including dismissing those who fail to discharge their legal duties or exercise requisite care and attention.

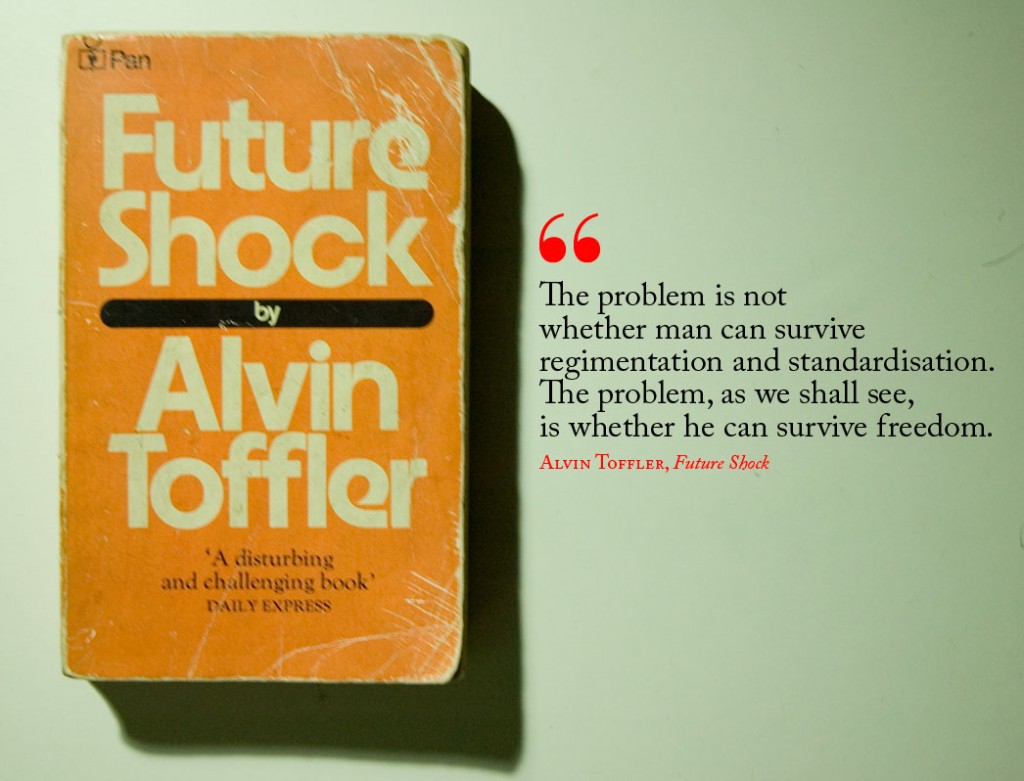

In 1970, Alvin Toffler's book Future Shock was published. It quickly became a bestseller. Toffler died recently, triggering a series of articles and reflections (including this one published in the New York Times) about his life and 'the book'. Toffler had an amazing ability to look well ahead of almost all of us, to think critically, and to make some sense of it all. Consider these observations by Manjoo in his reflection: Alvin Toffler ... warned that the accelerating pace of technological change would soon make us all sick. Yet in rereading Mr. Toffler’s book, as I did last week, it seems clear that his diagnosis has largely panned out, with local and global crises arising daily from our collective inability to deal with ever-faster change. That societies are racing with great speed to embrace new ideas and innovations, yet without the ability to cope with the consequences of high rates of change, might be one of the great problems of our age. Perhaps those in influential positions in society have a responsibility to shift their gaze, from their own ambitions towards altruistic ideas that serve the greater good? This is by no means a call to embrace utopian principles nor uniformity because we are all different. Much pragmatism is needed if society is to continue to endure. Leaders—of all types but especially business leaders, company directors, politicians and academics—could do well by (re)reading Future Shock. We need to talk about stuff, because we all have much to learn.

Guest blog: Tim Sillay (Wellington, New Zealand) I'm angry. It appears that as a society, we are hell bent on eliminating risk. There doesn't appear to be any sensible discussion on acceptable levels of risk, witness the current implementation of the health and safety legislation. When you see a site board on a building site list 'uneven ground' as a hazard, it is obvious that things have become seriously retarded. Now I'm not saying we should stand idly by and watch people bury depleted uranium, or leave boxes of dynamite laying around school playgrounds, but these futile attempts to wrap the world in cotton wool are breeding entire generations with no ability to assess or manage real world risk. What it is breeding is an entire generation of 'non-producers', paper shuffling bureaucrats whose job it is to police this whole mess. Let's face it, we've cut down all the trees in the playgrounds and removed all the really fun playground equipment, so little Johnny has no idea that walking on a slender branch will eventually result in hard contact with mother earth. You can't play bull rush or ball tag, so he also has no idea that fast moving people or things really hurt when they hit you... How are you going to figure practical application of geometry if you don't live the dream of 'tangent to the arc' on the witch’s hat? How do you figure out that some kids are better at sport, some are better at math and some are just plain stupid if everyone gets a certificate for participation. So by the time Johnny has completed his tertiary education and graduated with real world skills in something like coffee making, subsequently sued his employer for allowing him to come into contact with a hot cuppa and taken a nice safe office job as a health and safety inspector in an egalitarian agency where everyone has an opinion and everyone’s opinion matters, little Johnny, with no ability to judge what is and is not a real world risk, with no concept that someone may be smarter, more experienced or just plain crazy is the man who may eventually rise through the ranks and craft policy. With no one to argue the toss, the policy pendulum has swung firmly to the outer limit of 'no risk is acceptable' and 'all people are equals'. Which is patently ridiculous. This is just not the way the world works. This is what happens when as a country, you stop producing things. You lose the generational memory and experience of what it means to balance risk and reward. You forget that some people are good at thinking about stuff and some people just like to do stuff. The western world would not exist if it was settled under this legislation. When the thinkers start mandating to the doers, or the doers revolt against the thinkers, when you reach a point in the development of civilisation where no injury, code violation or upset feelings shall go unpunished, you are, quite frankly, fucked. But here I find a startling double standard. Let's start with a Saturday evening some three weeks ago when I received the unsettling news that a wonderful lady and long time acquaintance of ours had been murdered by her friend. Shock, disbelief, anger but most of all a sense of a grand imbalance in the fabric of the world. How can such a gentle girl have met such a violent end? What possible sequence of events led to this? How did we as a society so obsessed with the elimination of risk let this happen? And there it was, that of which we shall never speak, our old bed fellow mental health. Over the last 30 years as we moved inexorably towards this sham world of universal acceptance, equality, tolerance and non-productivity we forgot that crazy people are actually crazy. Somewhere, in spite of all the signs to the contrary, we forgot all about unacceptable risk. I fail to see the chain of logic symbolised by these responses:

Somewhere, the policy wonks ran riot over the doers, those who lived the reality of day-to-day life with the insane. I can hear the sharp intake of breath. I can hear the agonised humanitarian wails of "You can't say that". I can even hear the bean counters rationalise it on a cost basis. I bet if you listened carefully, on a quiet day where the wind is blowing in just the right direction, you'll find an actuarial report that rationalises the occasional damaged child or other collateral damage about a crazy person gone off the rails. But you'd better be whispering. We NEVER discuss this kind of thing in polite society. So here's a brief history lesson. Teenage Suicide. It was a bloody epidemic in the 80's. I lost several from the circle and it hurt. It hurt a hell of a lot. Witnessing the grieving parents of a teenage girl will stay with me forever. It was more horrendous than the senseless killing of my friend by a crazy person, in as much as there is a scale for these things. It obviously was a problem, it obviously wasn't acceptable. So what did we do as a society? WE STARTED TALKING ABOUT IT. So I applaud the news that Coroner Michael Robb is conducting an enquiry into mental health related killings. Long may it make front page news. Maybe, just perhaps, this senseless, vile, unfathomable thing is the point where we all cry ‘enough’. Guest blog: Tim Sillay (Wellington, New Zealand)

Busy-ness seems to be a fact of life for many people these days. Whether it is running between commitments, as a business person, as a parent or anything in between, downtime has become a precious commodity—one to be treasured and nurtured. Modern conveniences like unlimited wifi (including on some flights nowadays) mean we are never far away from activity and doing things that, in our own mind at least, add to our personal sense of worth. While busy-ness can be a good thing, more often than not sustained periods of busy-ness will lead to reduced effectiveness and possibly even burnout or breakdown. We get so wound up doing stuff that our world closes in around us, until we lose sight of 'why'—our True North. Loosing perspective is not good for us, or those around us. As a senior executive or company director with significant responsibilities, you no doubt have a busy schedule. How do you keep things in perspective to ensure that you are actually effective in your work? Do you have an anchor, a True North, and do you referencing back to it? For me, downtime is the key to effectiveness—slowing the heart rate; getting away from people; taking time out to explore ideas (that would not normally even register on my everyday radar); and, in so doing, remind myself of what really matters, my True North. I do that by reading. Here's a selection of the books currently on my reading list. If you read as a means of maintaining your perspective, I commend them to you. PS: What you do to keep track of your True North doesn't really matter. Go for a walk, paint, read, sew, draw or whatever else takes your fancy. That you are taking time out from the busy-ness of life is what will make the difference to your effectiveness—as paradoxical as that may seem.

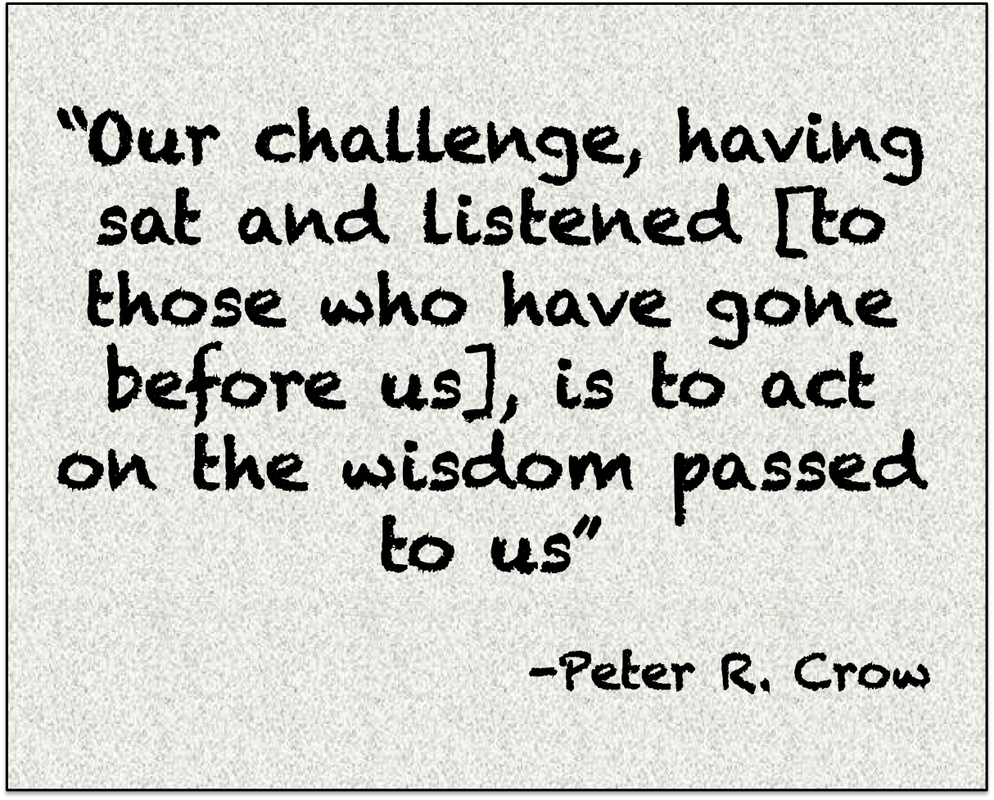

One of the biggest shake-ups to confront the Western World (since the collapse of communism and the fall of the Berlin Wall anyway) occurred in the United Kingdom last week. The result of a much anticipated plebiscite was a decision by the British people to leave the EU. In the weeks leading up to the referendum, the flow of information became a cacophony as politicians, scaremongers and other 'experts' promoted various positions, in an effort to influence to voting public. Finally, the day arrived and the people voted. Soon, the results were published. The people had spoken. Some cheered while others mourned. Curiously, some reacted by rueing their decision, wondering whether they had voted wisely. Really? With a straightforward question to answer and a plethora of information to hand, how could anyone make the 'wrong' choice (unless they didn't vote, of course)? Is this reaction an outpouring of buyer's remorse on a national scale, or is something else going on—an indication that some did not take the decision seriously or that a dose of hubris clouded the better judgement of some voters perhaps? The British plebiscite highlights a behavioural weakness that besets many people. From an early age, we spend our lives learning as much as we can, aspiring to become experts in whatever field interests us. Most of us want to excel; to realise our potential. In our haste to make decisions and get ahead, we tend to embrace new ideas and disregard 'old' ones. If we can secure an advantage, we'll take it—thank you very much. But when it comes to big decisions, we may not be as smart as we think we are. Decisions that are based on politically-motivated or emotion-filled pleas, or knee-jerk responses seldom deliver the 'best' outcome. Often, the best decisions are those made after we have paused and looked back, for guidance about how best to move forward. Whether we are cast as leaders or followers, we could do far worse than to seek out people like Bill and Augusto, sit with them and, having asked them a question, listen intently to what they have to say. Our challenge, having sat and listened, is to act on the wisdom passed to us.

|

SearchMusingsThoughts on corporate governance, strategy and boardcraft; our place in the world; and other topics that catch my attention. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

|

Dr. Peter Crow, CMInstD

|

© Copyright 2001-2024 | Terms of use & privacy

|